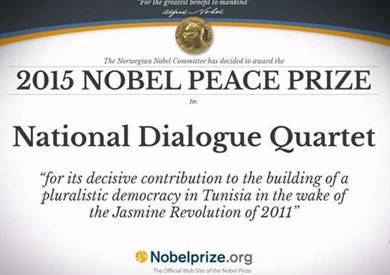

The Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies congratulates the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize this year for its crucial role in building a pluralistic democracy in Tunisia. The Quartet was nominated for the prize by the elected president of Tunisia, Beji Caid Essebsi.

The Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies congratulates the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize this year for its crucial role in building a pluralistic democracy in Tunisia. The Quartet was nominated for the prize by the elected president of Tunisia, Beji Caid Essebsi.

Representing civil society and rights advocates, trade unions and professional syndicates, and businessmen, the National Dialogue Quartet comprises the Tunisian Human Rights League, the Tunisian General Labor Union, the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade, and Handicrafts, and the Tunisian Order of Lawyers. The quartet managed to achieve a consensus among disparate political factions after political tensions peaked in 2013. The crisis threatened a breakdown of the assembly elected to write the country’s new constitution and the unleashing of a wave of political violence even as some parties urged the Tunisian army to intervene. The crisis was precipitated by rising tension between the National Salvation Front, representing Tunisian secularists, and the ruling Troika composed of the Islamist Ennahda Party and two of its non-Islamist allies, al-Takatol and the Congress Party.

The acceptance of state and security institutions, as well as Ennahda, of the outcome of the marathon talks led by Tunisian civil society averted a breakdown of the democratic transition and the associated disasters currently afflicting all other Arab Spring countries.

The year 2013 was not the first time that Tunisian civil society had advanced pragmatic solutions and set forth a roadmap to enable the country to avoid a setback in democratization.

After the revolution, the Tunisian state fostered a climate that enabled the High Committee to Achieve the Goals of the Revolution to perform its role. A body that expressed the most important components of Tunisian civil society, the committee functioned as the political and legislative engine in the country until the first general elections—a period in which the public sphere was liberalized and democracy proved victorious.

In this period, Tunisia adopted laws liberalizing civic action, appointing a permanent election body and requiring equal representation for men and women on electoral lists, and liberating the press and audiovisual media from the grip of the police state. Meanwhile, political regimes in other Arab Spring states were fostering conflict between various factions and even sexually assaulting women involved in public life, on the pretext of examining their virginity.

Tunisia demonstrated responsibility and a moral and political awareness in 2011 when it unleashed civic action and opened the public sphere to civil society, thus allowing them to mature politically. Less than two years later, civil society helped Tunisia to avoid the fate of other Arab states like Syria, Iraq, Libya, Yemen, and Egypt, where the political and security establishment was busy trying to quash civil society and smear it as a partner to global conspiracies seeking to divide the country.

The acclaim won by Tunisian civil society—rights advocates, labor unions, and businessmen—can perhaps stand as a rebuke to other Arab countries that chose to suppress civil and political society to protect sclerotic, authoritarian regimes at the expense of comprehensive, sustainable development that could lead to greater progress and prosperity.

The Tunisian people are honored on the same day that UN envoy to Libya Bernardino León managed to reach an agreement among warring Libyan factions on the formation of a unified national government. This is an important step that can stop the slide into civil war and the partition of Libya.

Libyan parties could not have reached this agreement without international support and mediation, not only because of complex military calculations and because some Arab states are actively attempting to divide the country by encouraging military action rather than political accommodation, but because Qaddafi so thoroughly hollowed out the public sphere over his nearly 40 years of rule. In the period, he sought to eliminate Libyan civil society, which could have taken action to address conditions before they reached the current impasse.

The fact that Tunisian civil society received this high international honor from a non-Arab party only demonstrates the narrow political vision of most current Arab regimes, which has had catastrophic consequences in Somalia, Sudan, Libya, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. The rare enlightened examples in the regime, like Tunisia, remind us of the lost opportunity for change and development.

Tunisia still faces major challenges and a heavy legacy of economic and political problems, as well as security challenges related to the deteriorating humanitarian situation in neighboring Libya. But the Nobel Peace Prize not only reminds the Tunisian state of the correct path to follow when facing the challenges of transitional justice, violent extremism, and the promotion of human rights. It also sends a message to Arab peoples that the correct path is one of dialogue, freedom, and solidarity based on acceptance of the right to differ.

Share this Post