Joint UN submission by rights groups exposes endemic torture and appalling conditions in Egypt’s prisons

Harrowing testimonies of systematic torture continue being too frequently heard as the date for Egypt’s Universal Periodic Review (UPR) approaches; Egypt’s review will take place on the 13th of November 09-12.30 Geneva Time. Allegations of torture have spiked especially in connection to the wave of arrests following demonstrations in late September (more than 4000 were arrested during less than one week). The cases of torture inflicted on, and testified by, rights lawyer Mohamed al-Baqer, blogger and activist Alaa Abdel Fattah, and journalist Esraa Abdel Fattah are but only a small fraction of the many verified testimonies detailing torture and cruel treatment over the last five years.[1]

Not only do the Egyptian authorities use torture to extract false confessions from persons forcibly disappeared in unofficial detention sites; they have also expanded the use of torture in formal detention sites, particularly against political opponents, as detailed in a joint report on torture submitted to the UPR last March by Egyptian and international rights organizations.[2] From 2014 to the end of 2018, 449 prisoners died in places of detention, 85 of them as a result of torture, as documented by the report. These numbers don’t include those who died from intentional medical neglect and an often prolonged denial of vital healthcare, a regular practice in Egyptian prisons that is critically threatening the life of former presidential candidate Dr. Abdel Moneim Aboul-Fotouh, the head of the opposition party Strong Egypt, who has been detained since February 2018. Medical neglect also caused the death of former President Mohamed Morsi in June.

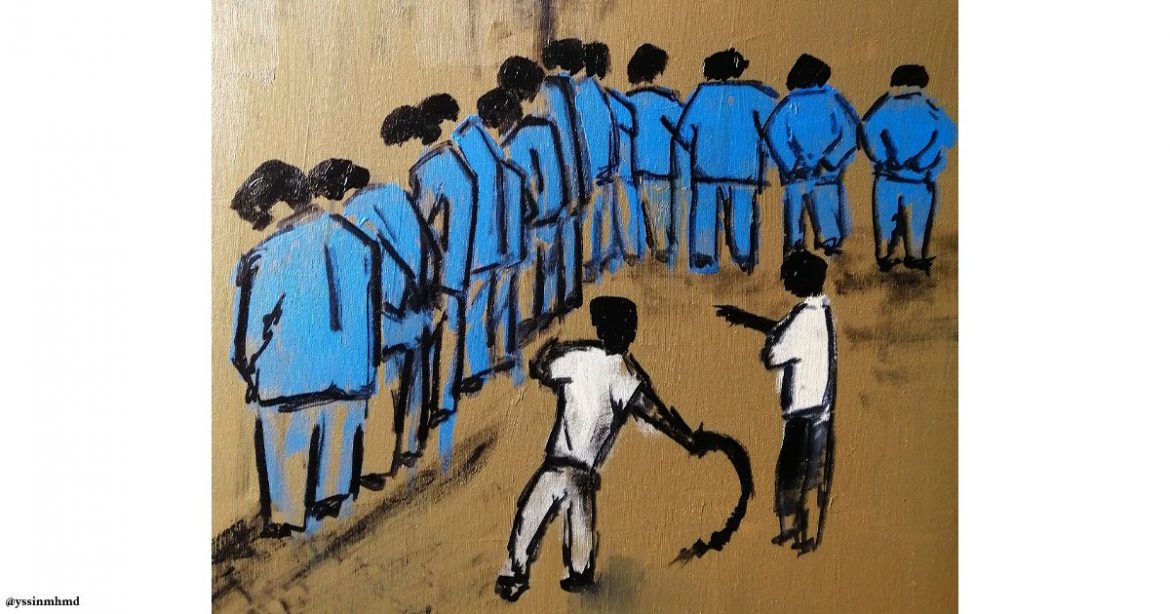

Given the widespread and systematic use of torture reported, it is unavoidable to assume that the highest levels of the Egypt government have greenlighted such practice, while at the same time shielding perpetrators from accountability, particularly when torture victims are political dissidents. In other words, torture is no longer a crime falling under individual culpability, but rather, it has become a state policy with the objective of deterring –by instilling fear - citizens’ participation in the public sphere. This is evidenced by recent amendments in legislation, in particular to the Counterterrorism Law, which made it legal to detain people for 14 days—later amended to 28—before bringing them before the investigative agencies; thereby lengthening the timespan under which there is no formal accountability for any crimes committed against detainees typically held in incommunicado in undisclosed locations. At the same time, the state has failed to adhere to its pledges to redefine the crime of torture in line with the Egyptian constitution and the Convention Against Torture—in fact, it has prosecuted rights activists who have sought to do so.

Alongside Egypt’s legislative system, Egypt’s judicial system enables systematic torture. The Public Prosecution, particularly the High State Security Prosecution, colludes in covering up torture and protecting perpetrators. The joint report on torture documents cases in which defendants reported torture to the prosecutor, and the prosecutor ignored or failed to investigate the allegations.[3] Courts disregard defendants’ allegations of torture used to extract confessions; and sentence to defendants to prison or even to death on the basis of confessions coerced under torture. In this respect, the report’s findings are similar to those of with the United Nations’ Report of the Committee Against Torture:

“Torture appears to occur particularly frequently following arbitrary arrests and is often carried out to obtain a confession or to punish and threaten political dissenters. Torture occurs in police stations, prisons, State security facilities, and Central Security Forces facilities. Torture is perpetrated by police officers, military officers, National Security officers and prison guards. However, prosecutors, judges and prison officials also facilitate torture by failing to curb practices of torture, arbitrary detention and ill-treatment or to act on complaints. Many documented incidents occurred in greater Cairo, but cases have also been reported throughout the country. Perpetrators of torture almost universally enjoy impunity, although Egyptian law prohibits and creates accountability mechanisms for torture and related practices, demonstrating a serious dissonance between law and practice. In the view of the Committee, all the above lead to the inescapable conclusion that torture is a systematic practice in Egypt.”

The rampant proliferation of torture and its transformation into state policy has normalized the crime in Egypt; altering victims’ perceptions of its severity. Many no longer consider kicking, slapping, threats, and psychological harm to be torture; only electroshocks, whipping, or brutal assault or violence causing substantial harm or major disability are considered torture.

In this context, the report addresses the numerous types of torture inflicted upon detainees, particularly persons charged in political cases. These include enforced disappearance and incommunicado detention, and filmed confessions coerced by torture, duress or threat, which are then used as propaganda films produced by the military or Interior Ministry.[4]

Egypt’s upcoming UPR may be the final opportunity to implement the report’s recommendations to counteract torture. These include pressuring the Egyptian government to allow UN experts—particularly the UN special rapporteur on torture and the special rapporteur on counterterrorism and human rights—to visit Egypt, as well as to permit the International Committee of the Red Cross and relevant national and international NGOs to visit and inspect detention sites. The Egyptian government should also create a national preventive mechanism composed of independent rights organizations authorized to make unannounced visits to detention sites to ensure that torture is not being practiced.

At the same time, the UN and the international community should pressure Egypt to ratify the Optional Protocol to the UN Convention Against Torture and join the International Convention on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

[1] Some of those who have given statements refuse to reveal their identities in fear of reprisals that could bring additional torture or more severe detention conditions.

[2] The NGOs are: Committee for Justice, Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS), DIGNITY – Danish Institute Against Torture, El Nadeem Center for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence (El Nadeem), Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms – Europe (ECRF - Europe). And due to reprisals and threats faced by human rights defenders on a daily basis in Egypt, Another NGO contributing to this report opted to remain anonymous. The group is henceforth referred as the Coalition.

[3] At best, persons alleging torture are referred to a forensic examiner long after their torture to ensure that no physical traces remain

[4] One of many examples is the recent one of a group of students and foreign tourists arrested in central Cairo. Egyptian media aired videos of them confessing under duress to taking part in an international conspiracy to foment chaos in Egypt. The falsity of these claims was proven days later, and they were released and allowed to return to their home countries.

Index

Joint-submission on the Right to be free from torture and ill-treatments

This is an informal coalition of NGOs and INGOs that have covered issues related to the right to be free from torture and the victims’ right to reparation in Egypt since several years. Some of the members of the coalition have formally coordinated, among others, on previous submissions to the UPR as well as on side-events to sessions of the UN Human Rights Council. Most importantly, this Coalition has been coordinating since 2013 on the attempt to dialogue with the relevant Egyptian authorities as well as with all UN relevant stakeholders to demand the realization by Egypt of its obligations to respect, protect and fulfill the right of all Egyptian citizens as well as others under Egyptian jurisdiction to be free from the practice of torture and ill-treatments. The members of the Coalition are:

A. Description of the methodology and consultation

This report has been prepared by a network of national civil society organisations and international NGOs focused on the prevention of torture and access to justice, including redress for the victims and the prevention of enforced disappearances. The organisations that participated in drafting this report are: , CIHRS, Committee for Justice, DIGNITY, ECRF- Europe[1] And due to reprisals and threats faced by human rights defenders on a daily basis in Egypt, Another NGO contributing to this report opted to remain anonymous, The group is henceforth referred as the Coalition.

The report has four sections (A, B, C, D) and focuses on seven key issues pertaining to the right to be free from torture and other forms of ill-treatment as regulated by the UN Convention Against Torture (CAT); moreover, recalling the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance as well as the international jurisprudence[2], this report considers all cases of enforced or involuntary disappearances as a case of torture.

In its final section (D) the report delivers the Coalition’s recommendations to all relevant authorities in Egypt.

All data and information presented in this report are the results of testimonies, monitored cases and media archives directly gathered by the members of this Coalition independently or in coordination; subsequently most significant data were merged into this report.

B. Developments since the 2014 UPR review

During the last UPR review in 2014, 31 out of the 300 recommendations that were made to the Egyptian government related to torture. Egypt specifically rejected recommendations to ratify the Optional Protocol to the CAT (OPCAT) and to invite the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture.

Pointing out that torture was a crime under its national law, in 2016, the Egyptian delegation reported that there was no torture in its prisons.[3]

Notwithstanding, monitoring reports issued by this Coalition since 2014 consistently indicate that: torture is a systematic practice in Egypt both in official and unofficial places of detention; independent or effective monitoring of conditions of detention is practically absent; and, that claims of torture are virtually not investigated while the judiciary has increasingly lost its independence. The prevalence of enforced disappearances (ED) is singled out as having dramatically increased since the last UPR review in 2014.

In June 2017, the Committee Against Torture (the Committee) published the Summary account of the results of the proceedings of the inquiry on Egypt as part of its Annual Report; the Committee reached “the inescapable conclusion that torture is a systematic practice in Egypt”[4].

Egypt has not submitted a report under its obligations per the UNCAT since 2002 (Cycle IV), rendering Cycle V 14 years overdue.

The findings of the report at hand indicate that the cases are many. During the period 2015-2018, a member of the Coalition received a total of 453 clients, out of which 95 were subjected to torture and 103 subjected to police violence outside of a detention setting. Media archives covering the period 2015-2018 point to a total of 1,854 cases of individual ill-treatment/torture in detention. According to the media archive, 449 prisoners died in places of detention, out of which 85 died as a result of torture.

The widespread use of torture has influenced people’s perception of what constitutes torture to the extent that former detainees no longer consider slapping, kicking or beatings (not causing serious injury) to amount to torture and, accordingly, only report such treatment when asked in detail. Complaints are usually instigated when torture involves electrocution, stripping, threatened or actual rape with an object, suspension or inverted suspension from a hinge, soaking in cold water, food and water deprivation or threats to cause harm to the family among others.

Many detainees, especially from Islamic affiliations, are shown on video confessing to crimes after periods of disappearance, while some of them show signs of duress on their faces. One example of this involved lawyer and human rights activist Ezzat Ghoneim, Director of the Egyptian Coordination for Rights and Freedoms, who was shown on a video making confessions after a period of enforced disappearance.

Months later after an order of release by the competent judge he has gone disappeared (from September 2018 to February 2019). Mr. Ezzat was seen by ‘coincidence’ by a lawyer of this Coalition at a hearing of Cairo Criminal Court on the 9th of February. Since then Mr. Ezzat is held in incommunicado detention.

C. Specific Issues

1. Criminalisation of Torture [5]

In the summary of the deliberations of Egypt's comprehensive periodic review of the UN Human Rights Council, Ambassador Hisham Badr pointed out, that “the Supreme Committee for Legislative Reform is currently studying a number of laws and a definition of torture consistent with the Convention against Torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment”[6].

The criminalization of torture under the Egyptian law falls well short of adhering to international standards, particularly in terms of definition and punishment. Specifically, under Article 126 of the Egyptian Panel Code, torture is limited to acts inflicted with the purpose of inducing confessions from accused persons, excluding therefore acts against those detained without charge, and for the purposes of obtaining information or punishment. Article 126 (following its amendment in 2003) foresees imprisonment between 3 and 10 years, and in the case of death the punishment of homicide applies, but since the article has a limited scope, prosecutors charge perpetrators of “use of cruelty” under article 129 of the Penal code which provides a range of penalties in the case of conviction of up to one year of imprisonment or a maximum of 200 Egyptian Pounds, that is clearly inadequate and contrary to national and international law[7].

Because officers are not initially charged of torture by prosecution, instead they are charged of “use of cruelty” or “manslaughter” in case of death not “voluntary homicide” – this leads to lenient sentences.

In its UPR Midterm Review, the Egyptian Government stated in point 21 that the Egyptian constitution stipulates that “all forms of torture are a crime with no statutes of limitation” and that the “state will fairly compensate those who have been assaulted”. However, the Constitution in its article 52 only states that “Torture in all forms and types is a crime that is not subject to prescription”. Broadly, according to the CAT, it is not sufficient to solely have a prohibition in constitutional law.[8]

Despite these clear shortcomings, Egypt has not legislated – nor has its parliament discussed – a special stand-alone law against torture since 2014.

In fact, when a draft law on torture was proposed by human rights lawyer Nejad Al Borai with the technical advice from two judges in the highest judicial posts; one of whom was the vice president of the Court of Cassation, and the other president of Cairo Court of Appeal, the initiative was negatively received by Egyptian authorities. The two judges were referred to the Disciplinary Board to be tried on charges of expressing political opinions prohibited to judges (even though their role was limited to providing advice). Nejad Al Borai, who submitted the draft and sent it to the President of the Republic in May 2016, was banned from travelling abroad, and charged with, inter alia, the establishment of an unauthorized group, and receiving funds from abroad.

2. Prompt access to a lawyer and access to a medical examination by an independent doctor

According to Egypt’s national report[9] under the second cycle of the UPR, the national law guarantees the right of immediate notification of the reasons of arrest as well as the right to legal aid.

Evidence collected by Coalition’s lawyers and researchers demonstrate that detainees who are subjected to torture, especially those who are disappeared, do not get access to a lawyer when they are presented before the prosecution where they hear the victims’ accounts for the first time. Importantly, the Prosecution usually denies the victim’s right to report any ill-treatment to which detainees may have been subjected.

An example is provided by the case involving human rights activist and lawyer Hoda Abdelmoneim and the daughter of MB leader Khairat El Shater, Aisha, together with a group of 11 other women (case 1552/2018). When they reappeared in front of the prosecution they all testified that they had already been interrogated while denied the presence of a lawyer. The same happened with human rights lawyer and activist Ezzat Ghoneim who was arrested, disappeared, reappeared, ordered release by a court and then disappeared again, while the Ministry of Interior posted a video of his confession in an illegal process where he was denied the presence of his lawyer (see also text above).

The testimonies collected from victims of torture prove that they do not usually get access to a medical examination following their request to the prosecution, as the prosecution refuses to refer them to the Forensic Medical Authority to examine their health conditions. In some cases, the prosecution delays the referral to the Forensic Medical Authority until the physical marks of torture disappear. Generally, there is no access to independent forensic doctors at any stage of the arrest’s period.

A member of the Coalition has received several clients who indicates that in spite of their explicit request for forensic examination, this is denied by the prosecution. An example is Islam Khalil who was suspended for long periods of time during his first arrest and disappearance for 122 days. Despite his request he was never examined. When released and investigated he had major affection of his brachial plexus on both sides.

A separate problem is that during interrogation by the prosecution a state security officer is usually present to ensure the defendant says what has been agreed; in the rare cases where referral is made to forensic examination the victim is accompanied by a police officer.

3. Confessions obtained by torture [10]

Article 55 of the Egyptian Constitution confers any accused person with the right to be free from torture and to be treated with dignity as well as the right to remain silent and provides that any statement that is proven to have been given by the detainee under any conditions stated by the article (including torture, coerced or physically or mentally harmed) shall be considered null and void. Moreover, Article 40 of the Criminal Procedure Code states that “No person may be arrested or incarcerated unless by virtue of a warrant issued from the legally competent authorities. Persons shall be treated with dignity and may not be physically or morally abused”.

However, the actual legal procedures do not usually protect detainees’ rights from forced confessions; in fact, the detainee who is forced to make confessions under torture should report the instance to the prosecution which, in turn, should file a new case to investigate the ill-practices made by the security officers to prove the instance of torture. Prosecution authorities in Egypt usually denies detainees the right to file this kind of complaint, which makes it difficult for a victim during the trial to prove that the confessions were made under torture. Moreover, in some cases, especially if the accused has a political background or related to issues of national security, judges arbitrarily convict the accused persons even when they reported that their confession were made under torture.

The Coalition monitored and directly observed 31 cases in order to record various forms of torture, wherein the arresting authorities forced the accused to confess to the charges through physical and psychological means. The documentation available indicates that a total of 212 defendants (belonging to 31 separate cases) were subjected to various forms of torture and other forms of ill-treatment. The statements of 212 defendants reveal that they were exposed to one or more forms of torture combined, as follows:

- 132 were subjected to physical beatings with hands, legs or sharp instruments by the arresting authority, or in places of secret detention;

- 89 were subjected to electrocution;

- 26 were subjected to hanging from hands or feet; and,

- 70 were threatened with torture or assault on their families.

From the 212 accused, the prosecution referred only 88 defendants to forensic medicine following allegations of torture and failed to act on 124 requests for referral to forensic medicine.

An illustrative example of the use of confession extracted under torture is found in the death sentences handed down against nine young persons who confessed to being involved in killing Hisham Barakat, the former General Attorney. Notwithstanding the defendants’ claims that the confessions were induced by torture and that some of the defendants exhibited visible marks as corroboration, they were executed on 20 February 2019 on the basis of their tainted confessions.

4. Effective investigations and complaints procedures [11]

Existing legal procedures as stipulated by Egyptian law neither ensure that victims of torture and their families are able to effectively obtain justice, nor that perpetrators are held accountable with the investigative authorities not prosecuting the perpetrators.

Article 232 of the Criminal Procedure Code prevents a civil party (a torture victim in this instance) to move lawsuit directly in court against civil servants and law enforcement officers in relation to offences (that would include torture or other ill-treatment) when the accusation made against them are related to crimes committed thereby during the course or as a result of performance of their job. Therefore, victims of torture (or their families in case of death) are not able to directly move a lawsuit against civil servants or law enforcement officers (this is also in disregard of the principle of article 99 of the Constitution). Hence the law authorises only the Office of the Prosecutor General to make the final decision to refer a case against a public official or law enforcement officer to trial. In most of torture cases reported to the prosecution, perpetrators are usually sent for internal ministry discipline, dismissed, or cases are closed.

Before complaining to prosecution of having been tortured, victims of torture have to consider possible reprisals against them by the police or national security officers especially if they remain detained accused in a criminal case or a state security case. Families of victims and witnesses may also be threatened by police so that victims drop complaints they made. Victims of enforced disappearances are even more vulnerable to such reprisal as they are conditioned during their disappearance period not to say to the prosecutor that they were tortured or they will be tortured again. Furthermore, often victims of torture are blindfolded during torture, especially at National Security premises, and therefore victims do not know the name of a specific officer that they may accuse. In case of torture by military staff, military prosecution has jurisdiction, which is under the control of the Ministry of Defence, therefore military officers are virtually immune in case they commit torture or other ill-treatment.

In 2014, during the interactive dialogue, the Egyptian delegation said that “the Egyptian authorities were fully committed to the principles of accountability and the rule of law. All allegations of human rights violations and crimes were investigated, so as to ensure that perpetrators were brought to justice”[12].

Due to its systematic failure to investigate allegations by defendants in criminal cases, the Office of the Prosecutor becomes an accomplice in the use of torture. To the failure of investigating allegations, obstructive practices are added such as the systematic delay of referrals to forensic medicine. Such delays make the forensic report unreliable for the identification of initial physical injuries and their cause. The forensic report linked to case no. 4757 of 2014, Misr Al-Jadida felonies, evidences this issue. Therein, the report states that “the original features of his injury have changed with their healing developments and healing factors, so the nature and date of occurrence cannot be determined”.

5. Enforced disappearances (ED)

The widespread prevalence practices of prolonged incommunicado detention, secret detention and enforced or involuntary disappearances of people arrested by the Ministry of the Interior, including the National Security Agency, and by the Army raise major concerns.

The coalition has documented that almost all victims of ED, who spent more than the initial 24 hours detention before being brought before a prosecutor, were subjected to torture or other ill-treatment with the purpose of seizing a confession.

According to article 36 of the Code of Criminal Procedures, any arrested person must be brought before a prosecutor within 24 hours of arrest. The new counter-terrorism law (Law 94 of year 2015), in its article 40, allowed judicial officers to keep detainees in custody for an additional seven days based on an order from a prosecutor “in case of a terrorist danger”. In 2017, article 40 was amended and the seven days became 14 days that can be renewed once, so a detainee could be detained for 28 days on top of the initial 24 hours without appearing in front of a prosecutor. In fact, the practice is that the prolongation beyond 24 hours happens in an arbitrary form and detainees are not brought in person in front of a prosecutor before this extension.

Hence, the combination of a draconian law matched by arbitrary practices heightens the risk of secret detention and enforced disappearance and put detainees at an extra risk of being tortured or otherwise ill-treated without being able to report such violations to a judicial body.

ED are practiced widely in Egypt by members of the national security apparatus. The pattern normally entails the victims reappearing after varying periods of time, ranging from beyond 24 hours to three years, when they are eventually handed over to prosecution charged with terrorism related offences. In most cases, they are forced to render false confessions (as mentioned earlier). Some cases reappear in an official place of detention or presented to the prosecution only to be disappeared again. Some cases of ED were not followed by reappearance.

The families of victims of enforced disappearance established the Association of the Families of the Disappeared”, an association in 2013 to support each other in investigating the fate of their relatives. Egyptian authorities, however, attacked them and arrested one of its founders lawyer Ibrahim Metwaly, a father of enforced disappearance victim. In September 2017, Mr Metwaly was traveling to attend a meeting with the UN WGEID, when he was arrested at Cairo airport and made to disappear for three days at the premises of the National Security in Abassia. He was subjected to torture then brought before state security prosecution accused on founding an illegal group and liaising with a foreign organization and spreading false news, all related to his activism against enforced disappearances. Although he told state security prosecution of the torture he was subjected to, nobody was held to account.

In 2018 alone, the Coalition recorded 1.302[13] cases of ED with a period of 24 hours or longer. From 30 June 2013 to 30 August 2018, the Coalition recorded 1690 cases of ED involving a period of more than 48 hours (cases below 48 hours are not counted in this statistic). However, the Coalition stresses that there are many more cases which went undocumented due to the lack of capacity and the difficulties reaching the victims and their families. One Coalition member estimates that the documented cases of disappearances represent about 15% of the actually reported cases. Available statistics generally don’t include cases from the Sinai Peninsula which over the past four years has become inaccessible to any independent monitoring because of security and military operations conducted there.

An example of the pattern of forced disappearances is the case of Islam Khalil who in 2015 was disappeared for 122 days, reappeared in prisons and held in pre-trial for circa one year; following his release, Islam Khalil was disappeared a new time in March 2018; he eventually reappeared at a prosecutor’s office for interrogation 11 days after his disappearance. During his second un-official detention Islam Khalil was tortured. Finally, Islam Khalil was kept in pre-trial detention until February 2019 when following a release order by the competent judge Islam Khalil disappeared again for a month (from February 26th to March 26th).

6. Conditions of detention [14]

6.1. Overcrowding and physical conditions of detention

During and following the events of 30 June 2013, the Egyptian authorities arrested thousands of people en masse, especially after enacting the Protest Law[15] and a new Anti-terrorism law[16]. These oppressive policies led to a massive increase in the number of prisoners and detainees who are detained in overcrowded police stations and prisons that do not have the capacity. Expectedly, this resulted in thousands of detainees being trapped in inhuman conditions harmful to their physical and mental health.

Testimonies collected from prisoners in the last four years indicate that detention conditions have deteriorated, as cells have become overcrowded with lack of ventilation, basic hygiene, sufficient toilets and clean water. Detainees in police custody as well as convicted prisoners invariably report that authorities systematically resort to ill-treatment such as excessive use of disciplinary penalties, preventing prisoners from obtaining hygiene items, food, and clothes.

Almost every month there are at least two or three SOS calls in leaked letters from prisons, complaining of unjustified police raids of the cells where all the belongings, blankets etc. of the prisoners are taken away, without giving a reason. In the Tora supermax prison also known as “Scorpion” and in Tora high security prison (both belonging to the Tora Prison complex) the rule is that prisoners do not have access to personal hygiene items and only one blanket despite the cold of the winter.

6.2. Use of Isolation

In the last four years, the Egyptian authorities have increased the use of prolonged and indefinite solitary confinement against political prisoners for periods ranging between three weeks and over four years.

According to Article 44 of Law on the Organization of Prisons[17], solitary confinement is a disciplinary procedure and shall not exceed one week. The law was amended by a presidential decree in 2015 extending the permissible period of punitive solitary detention to 30 days for sentenced prisoners and up to 6 months in high security cases. In the latter case the prisoner is held in a high security solitary cell. The amendment sets the limit of solitary confinement - in cases where the procedure is not punitive - to 15 days.

The use of isolation by Egyptian detaining authorities is in direct violations the Nelson Mandela Rules setting the international standards for the treatment of prisoners.

The law and its rules specify the use of solitary confinement as a form of discipline; however, there is no mention of specific cases when such disciplinary measure should be enforced, hence leaving it to the discretion of prison officials.

According to some prisoners who were subjected to solitary confinement, this punishment is imposed following arguments with the officers or informants, after objecting against arbitrary orders, or explicitly used as a regular detention regime for political opponents. Furthermore, the collected testimonies of detainees who have been in solitary confinement prove that they were sent to dark cells with standard toilets, while not being allowed to leave the cell for any time or exercise. The room normally does not exceed an area of one per two meters when the solitary confinement is for disciplinary reasons. Otherwise it could be slightly bigger, but with no ventilation, the room is emptied of any contents/furniture and prisoners are only given a bottle of water a day. A former prisoner at Lehman 430 Wadi Natroun has relayed that: “The window is covered with additional layers of wire, so that no air or sun enters”.

- Abdellah Boumidan: a 12 year-old boy who spent six months in solitary confinement;

- Abdel Moneim Abul Fotouh: head of the Strong Egypt party, who has been in solitary confinement since he entered prison in February 2018;

- Mohammed al-Qassas: in solitary confinement since approximately a year ago; and,

- Ahmad Doma: who has been in solitary confinement since end of 2013.

Another problematic point is provided by the law No. 396 of 1956 which provides the supervision over prisons and places of detention to the Ministry of Interior via Prisons Director General and prisons’ directors. The law provides the Prisons Authority the right to execute humiliating and degrading disciplinary punishments, such as solitary confinement or putting the prisoner in the disciplinary room for up to six months.

The same law provides the prison general manager also with the capacity to cuff the prisoner leg inside or outside the prison or the places of detention as a precaution to prevent the prisoner from escaping.

6.3. Denial of medical support

In its midterm report, Egypt states that “measures have been taken to enhance detention rooms to reduce health risks for the detainees and measures taken to provide medical care. These are measures such as ‘providing adequate medical care both preventive and therapeutic to the prisoners through establishing a hospital for each prison, that include clinics of all specialties, as well as a central hospital in each prison district, and vaccinations against epidemics and diseases for prisoners”.

The Coalition has documented at least 347 cases of medical negligence in places of detention in 2018 alone. The denial of the right to health care is one of the major violations to which prisoners and detainees in Egypt are subjected. There is a lack of prisons’ clinics and other similar facilities and the existing ones usually have poor preparation. Prison hospitals usually do not have medical and nursing staff that can meet the need of the massive number of prisoners.

Doctors are not accountable to the Egyptian Medical Syndicate so much so that the medical association does not have a list of names of prison doctors. For this reason, the Medical Syndicate is prevented from exercising the required ethical control.

In a report covering 2014-2016, issued by a member of the Coalition, it is documented that there is no direct access to a doctor; the access to the doctor is screened by the guards, then the officer on shift then the prison administration then the clinic. Moreover, a doctor is available only during regular working hours (until 2 pm); after this time and on official holidays there is no doctor available and the paramedic is the one who prescribes medication, even to emergency cases.

The amended internal prison regulations, decree no. 3320/2014 at its article 37 stipulates that if the necessary medical requirements are not available in prison or the prison hospital, and upon recommendation of the prison doctor to transfer the prisoner to an external hospital, the doctor should report to the medical prison department to make a decision. In cases of emergency the doctor may undertake what he considers necessary for the health condition of the prisoner. This rule is not respected: since 2014 the coalition has reported at least 19 of patients with cancer that were not allowed to access specialized medical facilities and that died in detention due to medical negligence.

A case is provided by the testimony of a wife of a prisoner who stated in a press conference that her husband had suffered severe abdominal pains. He was referred to Kasr Al Aini teaching hospital when his condition deteriorated. While in the hospital, she was denied visits. He died of cancer stomach a few days after his transfer. She later found out that this diagnosis was made six months earlier and that the prison had withheld this information keeping the prisoner in prison until the final stages of his illness.

As a result of medical negligence the number of death in places of detention due to medical negligence recorded by the Coalition rose (81 cases in 2015, 80 cases in 2016, 74 in 2017 and 48 in 2018 according to the media archives).

The causes of deaths ranged from serious medical conditions which did not receive medical care such as cancer, liver or hepatic failure, down to easily manageable conditions such as infected wounds, fever, diabetic coma, diarrhoea leading to dehydration.

According to media archives, the numbers of those suffering medical neglect and resulting deaths in prisons in the period between 2015 to 2018 are as follows:

| Year | Complaints of medical neglect | Cases of death in detention | Cases of death in detention due to medical neglect |

| 2015 | 358 | 137 | 81 (59%) |

| 2016 | 471 | 123 | 81 (66%) |

| 2017 | 277 | 118 | 74 (63%) |

| 2018 | 236 | 71 | 51 (72%) |

6.4. Family Visits

Egyptian authorities continue to violate the national and international laws[18] that grant detainees the right to communicate with their families and friends. Many detainees’ families have reported that the administration of different prisons denied their legitimate visitation requests, even with the permission from the General Prosecution. The authorities have usually used the denial of visitation rights punitively. In some cases, visitation has been denied from several months to two years. The case of Mohamed Morsi, the former President of Egypt, is a case in point. After 2013, this practice became more systematic and directed at all detainees especially these who are held in pre-trial detention.

A Coalition member also reported in 2015 that the administration of seven prisons in Egypt have instituted hostile treatment against detainees’ families during their visit to their detained relatives, as they were insulted and subjected to humiliating inspection. They also reported that the prisons administration had shortened the visit duration to be 15 minutes instead of one hour as provided under the law and that they saw their relatives across barbed wire or a glass wall in other cases. The prison administration also inspected the food and allowed only one meal and canned fruits, sweets and books which were allowed before. In protest against these repressive practices, prisoners at most of the prisons in Egypt went on hunger strike, especially in Tora prison.

7. Independent Monitoring of places of detention [19]

Egypt has consistently rejected recommendations[20] [21] on the ratification of the UN-OPCAT claiming the instrument may raise legal issues regarding the quasi-automatic right to visit places of detention. Like during the first review none of these recommendations were accepted.

Egyptian law only gives competence to the Public Prosecutor to visit places of detention. Granting authority to other entities would be regarded as an interference in the affairs of the judiciary. The second reason for Egypt to reject these recommendations is the lack of a mechanism of international cooperation within the UN-OPCAT. Egypt firmly believes in the need for national capacity-building as an integral part of the UN-OPCAT.

As the recommendations were not accepted there were also no steps taken to implement it. No further comments on the UN-OPCAT were given in the stakeholder’s mid-term report.

Law 197 of 2017 represented a step forward. Article 3 of law 197 of the year 2017 amended the National Council for Human Rights (NCHR)’s law which gave it the right to inspect prisons, places of detention and prison hospitals. The NCHR is also granted the right to visit detainees and listen to their grievances and make sure that they enjoy their legal rights. NCHR drafts a report on each prison visit that includes their observation and recommendations to enhance detention conditions of prisoners. However, in reality the NCHR cannot perform neither independent nor credible monitoring visits.

In an interview George Isaac[22], NCHR member, said the mandate of the Council does not include carrying out unannounced visits to Egyptian prisons, except after obtaining a permit from the public prosecution, which in turn informs the ministry of interior, making the visit contained. In another interview he pointed out that “the prisons that are scheduled to be visited by a human rights body are notified of the date of the visit, and the prison administration ‘rearranges the prison to become a five-star hotel’ which is contrary to reality”.

Members of this coalition have requested several times the possibility to access places of detention, especially to deliver medical aid. Equally, this Coalition has shared several times the offer to enter into a partnership leading to establish a system of independent monitoring of places of detention, while respecting the spirit of the method of preventive monitoring that grants the State full confidentiality over the finding. Such offer remains dismissed. Today Egyptian authorities do not allow the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to access prisons.

Prisons remain completely secluded from external oversight and conditions of detention as well below any international standards – torture and ill-treatment thrive[23].

D.Recommendations:

- Establish a constructive ongoing dialogue with the UN Committee against Torture and with the Special Rapporteur on Torture on the implementation of the standards of the UN Convention against Torture.

- Take prompt and tangible actions to implement the recommendations of the UN Committee against Torture in the inquiry report, such as:

- To immediately end the use of incommunicado detention;

- Create an independent authority to investigate allegations of torture; enforced disappearance and ill-treatment; - Accept the mandate of the UN Committee against Torture to receive individual complaints (Article 22 of the UN Convention against Torture)

- Accede to the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

- Invite the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture to visit the country as well as the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism.

- Ratify the UN-OPCAT or in the absence of a ratification establish a National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) to conduct regular, unannounced, confidential visits to places of detention.

- Before the establishment of a NPM, strengthen the mandate of the NCHR according to Article 3 law 197 of the 2017 by allowing for independent and unannounced visit to places of detention.

- Allow access to places of detention by the ICRC as well as by specialised national and international NGOs to provide basic services related to health or to psychological support or delivering basic goods.

Footnotes

[1] See cover page for full name of each organization.

[2] See Celis Laureano v Peru, HRC, CCPR/C/56/D/540/1993 (1996), para. 8.5; Velazquez Rodriguez v Honduras, July 29, 1988, Inter-Am.Ct.H.R. (Ser. C) No. 4 (1988), para. 187; Quinteros v Uruguay, HRC, CCPR/C/OP/2 (1990), para. 14; Kurt v Turkey, 24276/94, European Court of Human Rights, para. 134.

[3] This was recorded in the Summary of the Proceedings from the review process of the 2nd UPR Cycle (Interactive Dialogue).

[4] A/72/44, para. 69 and 70.

[5] During the 1st cycle of the UPR five countries have made recommendations about the amendment or the harmonization of the Egyptian definition of torture with the definition used in the UNCAT: The recommendation by Japan (95.9); France (95.84); Germany (99.15); Spain (99.13) and Ireland (99.14). During the second cycle of the UPR Four recommendations were made on the harmonization of the UNCAT torture definition. Slovenia (112); Australia (113); Palestine (115) and Nigeria (114). All these recommendations were accepted by Egypt; Egypt stated during the interactive dialogue that the definition of torture was under review.

[6] Human Rights Council, Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review, Egypt, Twenty-eighth Session, paragraph 80, p A/HRC/28/16

[7] In preparation to the 1st cycle of the UPR Egypt pledged to review the definition of torture under art.126

[8] See e.g., Report to Togo, CAT/C/TGO/CO/1, para. 10.

[9] National report A/HRC/WG.6/20/EGY/1

[10] During the first cycle of the UPR review Switzerland (95.94) called upon Egypt to ensure that confessions obtained under torture are inadmissible. Egypt accepted this recommendation because it considered this to be already implemented or to be in the process of implementation. During the second Cycle of the UPR review a similar recommendation was issued by Uruguay (124). This recommendation was accepted.

[11] During the first cycle of the UPR Austria (95.35) and Switzerland (95.39) recommended that investigations to be effective and independent in a prompt manner and prosecution of those who committed torture. These recommendations were accepted by Egypt. For the second cycle of the UPR to ensure the investigation of allegations of torture and to ensure access to effective remedies for the victims was recommended by Botswana (122) and accepted by Egypt; France (179) recommended Egypt to ensure fair and independent judicial procedures in line with international standards; Ireland (180) made a similar recommendation; Canada (183) stated in its recommendation that a fair and independent judicial system is the pillar for a stable and democratic Egypt.

[12] Report of the Working Group A/HRC/28/16, 24/12/2014

[13] Only 399 of them had reappeared by February 2019.

[14] During the first cycle Switzerland made a statement during the interactive dialogue. It stated that thousands of persons are administratively detained without charge. As a follow-up to this statement Switzerland (95.83) also made a recommendation. They called up in Egypt to release those whom are administratively detained without a formal charge or to make them the object of an equitable trial. Egypt fully supported this recommendation. Chile (95.95) recommended guaranteeing access to detainees by lawyers, doctors and family. According to Egypt, this recommendation was already implemented or in the process of implementation. During the second cycle Switzerland (117) and Denmark (118) recommended Egypt to ensure protection against torture in places of detention. More specifically Denmark recommended that detention conditions meet the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners and the Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners (today’s Mandela rules). Ireland (180) recommended that the right to have access to a lawyer and family members as a detainee should be respected.

[15] Act 107/2013 signed into law in November 2013

[16] Law No. 94 of 2015 dated August 2015.

[17] Law No. 396 of year 1956.

[18] See inter alia UN Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment (1988), Principle 16: 1; UN Declaration on the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance, Article 10.2.

[19] During the first cycle of the UPR the Czech Republic (95.92) made a recommendation to allow the monitoring of the conditions in places of detention by independent entities. Egypt stated that this was already in place or in the process of implementation. During the second cycle Switzerland (116) called upon Egypt to establish a mandatory mechanism for independent visits to all places of detention. Egypt did not accept this recommendation. Egypt rejected this recommendation because only the Public Prosecutor is responsible for the surveillance of places of detention and shall make surprise visits on a regular basis.

[20] Gabon (5), Chile, Czech Republic, Sierra Leone, Switzerland, Togo, Tunisia (7), Austria (8) and Portugal (9).

[21] The recommendations were made by Switzerland (99.5), France (99.9), Czech Republic (99.3), Chile (99.8) and Brazil's (99.7)

[22] In an interview with the daily Masr El Youm, published on the 10th of October 2016; second interview given to Al Youm Alsabe.

[23] Prisoners are subjected to inspection by the Prison Service, and the prison administration, according to the Prisons Regulation Act. Article 83 of the Prisons Regulation Act refers to inspection of hygiene, health and security conditions. However, the inspections translate often into acts of punishment rather than into an attempt to improve conditions – during inspection prisoners are often beaten.

Share this Post