«A Web of Intimidation» Algerian Government's Global Crackdown on Dissenters

New Report Exposes Disturbing Trends in Repression Against Exiled Activists

26/11/2024

The Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS) published a report today that reveals the Algerian government’s expanding strategy of transnational repression, systematically targeting activists, journalists, and human rights defenders (HRDs) living abroad. The report, titled “The Noose is Tightening Around Us: Algeria’s Use of Transnational Repression to Crackdown on Dissent,” details the array of tactics employed by the Algerian government to silence dissent beyond its borders, drawing troubling parallels to authoritarian practices of countries like China and Egypt.

CIHRS’ investigation into Algeria’s transnational repression from 2020 to 2024 is based on 19 in-depth interviews with 21 exiled activists, as well as insights from their legal representatives and family members. It also includes a comprehensive analysis of primary sources, such as court documents, extradition requests, and reports from leading human rights organizations.

The Algerian government is increasingly pursuing activists abroad, targeting individuals who advocate for democracy and human rights. This isn’t just an isolated strategy; it’s part of a comprehensive campaign to suppress calls for change and impose strict control over narratives about dissent in the country.

The report warns that Algeria’s transnational activities aim to undermine activists’ voices where they may otherwise enjoy freedom of speech and safety from repression. Many of these activists reside in democratic countries, where they have access to platforms for open dialogue, challenging state narratives, and shedding light on governance issues. Yet Algeria’s reach extends to their lives abroad, ensuring that their dissent is met with intimidation, even in spaces typically safe from authoritarian control.

CIHRS documented several methods of transnational repression, including diplomatic pressure on foreign governments to detain or extradite activists, travel bans to restrict their movements, and targeted harassment of activists’ families and support networks within Algeria. These tactics form a web of intimidation designed to limit the voices of Algerian activists regardless of where they live.

Central to Algeria’s repressive strategy is its use of a conspiracy narrative that frames opposition as part of a foreign-backed plot to destabilize the nation. By labeling HRDs and activists as “agents” of hostile states, Algeria cultivates a climate of fear and suspicion to justify repressive measures. President Abdelmadjid Tebboune has repeatedly underscored this rhetoric, claiming foreign interference in protests and dissent. Following the fires in the Kabylie region in 2021, for example, he blamed Morocco and Israel for inciting unrest. State-controlled media echo these accusations, reinforcing the idea that activists, whether at home or abroad, are pawns of foreign powers—a false narrative that then permeates judicial actions against them.

CIHRS urges the international community to recognize Algeria’s actions as a growing threat to human rights and to implement immediate protections for exiled dissidents. Failure to address Algeria’s tactics would embolden similar authoritarian regimes, allowing them to extend repression globally and weaken democratic freedoms everywhere.

This report underscores the urgent need for coordinated international safeguards against transnational repression. As authoritarian states intensify their efforts to quash dissent beyond borders, the world must respond with concrete protections to uphold freedom of expression and safeguard human rights defenders wherever they may reside.

«The noose is tightening around us»

Algeria’s use of transnational repression to crackdown on dissent

Executive Summary

On 25 August 2021, at around 1 pm, men in plainclothes abducted Slimane Bouhafs, an Amazigh activist and Christian convert with a UNHCR refugee status living in Tunisia, in Hay Tahrir neighborhood, where he lived. For four days, the family did not know his whereabouts and feared that he had been forcibly disappeared by the Algerian or Tunisian authorities or non-state armed groups. On 1 September, he appeared before the investigative judge of the Sidi M’hamed tribunal in Algiers and was remanded in prison on six charges. In an official response to a United Nations inquiry about this case, Algerian authorities claimed that Bouhafs had voluntarily crossed the border between Tunisia and Algeria and was arrested by border guards. However, the circumstances of the case strongly suggest that he was abducted by Algerian authorities, possibly with the complicity of Tunisian authorities, and forcibly returned to Algeria where he faced spurious charges, an unfair trial, and torture. He was sentenced on 16 December 2022 to three years in prison on false accusations of spreading fake news and undermining Algeria’s unity; the sentence was upheld on appeal. He was released on 1 September 2024, after serving his sentence.

Bouhafs was the first documented case of Algeria’s new policy aimed at crushing dissent by widening the targets of its crackdown on activists, human rights defenders, and journalists to include those living outside of the country. After increasingly closing all spaces for dissent within Algeria since the suppression of the Hirak popular uprising in 2020, authorities have expanded their repressive reach to target dissidents abroad. This expansion reflects the regime's determination to silence opposition and maintain control, regardless of geographical boundaries. Dozens of other cases followed Bouhafs’ abduction, notably targeting activists who live abroad.

This report examines the transnational repression of human rights defenders (HRDs), activists, journalists, and political dissidents by Algerian authorities from 2020 to 2024. The Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS) conducted 19 interviews encompassing 21 cases with activists living abroad and their lawyers and family members. The research conducted for the report also comprises a comprehensive review of primary sources, including court decisions, extradition requests, and official statements from human rights organizations.

Transnational repression is employed by autocratic regimes worldwide to silence dissent beyond their borders. Countries such as Saudi Arabia, China, Egypt, and Russia have similarly targeted dissidents abroad, utilizing a range of tactics, including surveillance, harassment, and even abduction. Algeria's adoption of these measures reflects a broader international trend employed by authoritarians, where regimes seek to control and intimidate their critics regardless of their location. Activists abroad, particularly those residing in democratic states, often enjoy free speech and have the space to express their opinions. They can provide diverse perspectives, challenge official narratives, and criticize modes of governance actions that are difficult and dangerous for local activists. Transnational repression attempts to ensure the dominance of the authorities’ narrative. It stifles these voices and instills fear in activists abroad, potentially subjecting them to the same consequences for dissent as those within the country.

Transnational or ‘cross-border’ repression does not consist only of the prosecution of activists abroad and their forced return to Algeria to be imprisoned, whether through diplomatic pressure on foreign countries, coordination of repression efforts, or extradition requests and international arrest warrants. It also encompasses other tactics that the Algerian authorities exercise against their families, relatives, and support circles inside Algeria to pressure or force them to return to Algeria or stop their opposition activities abroad. In addition, activists residing abroad are prevented from leaving Algeria and returning to their places of residence if they come on temporary family visits in Algeria. CIHRS has found that there is a continuum between these tactics, all of which aim to trap activists within Algeria’s web of repression.

In Algeria as in other countries, this method serves to instill fear both inside and outside of Algeria within dissident communities, achieving the objective of suppressing any remnants of the Hirak movement, which began in February 2019 to demand radical political reforms. By targeting dissidents abroad, the Algerian government sends a clear message that no one is beyond their reach, thus deterring potential opposition and activism. Secondly, these extraterritorial actions help the Algerian regime promote its false conspiratorial narrative that the country is facing a network of criminal and terrorist entities operating within and outside of Algeria, which are undermining the security and unity of the state. This narrative justifies the regime's repressive measures, both domestically and internationally, by portraying itself as a bulwark against terrorism, instability, and foreign interference.

Activists, journalists, and dissenters who have sought refuge in other countries find themselves under relentless pursuit including threat of arrest and deportation, abduction, and intimidation, including through illegitimate extradition requests and diplomatic pressure on third states, regardless of the targeted person’s location. This underscores the drastic measures taken by the Algerian government to stifle opposition and maintain control, demonstrating that the repressive tools of the Algerian regime know no boundaries. Those targeted by these methods include prominent activists and participants in the 2019 Hirak movement, as well as individuals who speak out against government corruption and human rights abuses, or voice any other criticism of Algerian officials or the state.

In some of the cases documented by CIHRS, states were complicit in such extraterritorial repression. Mohamed Benhlima and Mohamed Abdellah, both activists and whistleblowers, were forcibly deported to Algeria from Spain where they were seeking asylum following an extradition request from the Algerian authorities. Spanish authorities deported them in a summary procedure, arguing that they represented a threat to security and to their ‘diplomatic relations with Algeria’, without providing proof that they were engaged in any harmful activities. Spain then sent them back to their country in total disregard for the non-refoulement principle, which prohibits surrendering a person to a place where they risk grave human rights violations. Upon their return to Algeria, both activists were tortured by Algerian military officers and sentenced to prison after unfair trials. Other countries refused to implement Algeria’s extradition requests and international arrest warrants, arguing there was insufficient basis for the allegations against these activists. Switzerland refused to extradite Mourad Dhina, a member of RACHAD, an organization that the Algerian government has arbitrarily classified as terrorist.

In addition to directly targeting activists, Algerian authorities have harassed and intimidated their families as part of a broader strategy to silence dissent. A notable example of this is Abderrahmane Zitout, the brother of political activist Mohamed Larbi Zitout living in the diaspora, who was arbitrarily detained and subjected to an unfair trial solely due to his familial ties. Targeting family members is a tactic designed to instill fear, isolate dissidents, and coerce them into silence, representing a blatant violation of international human rights standards.

The Algerian government has strategically employed a narrative of conspiracy to justify the widespread repression of HRDs and activists. Transnational repression plays a central role in framing opposition and activism as part of a broader conspiracy against the state, allegedly orchestrated by organizations with members both inside and outside Algeria. By labeling activists and HRDs as foreign agents or terrorists, Algerian authorities cultivate a climate of fear and suspicion, providing justification for repressive measures. President Abdelmadjid Tebboune has repeatedly asserted that protests and opposition activities are orchestrated by foreign powers seeking to destabilize Algeria. This was notably exemplified by his comments following the Djamel Ben Smail incident in the Kabylie region, where he blamed Morocco and Israel for instigating the events. State-controlled media reinforce this rhetoric by frequently portraying protesters and activists as pawns of foreign governments. Consequently, transnational repression unites activists both within and outside Algeria under a common set of accusations, allowing the government to perpetuate its conspiracy narrative through the judicial process.

Many human rights organizations[1] and United Nations mechanisms[2] have recently raised the alarm[3] about transnational repression[4]. However, much more effort is needed at the international level to prevent the weaponization of the legal and judicial systems by the country of origin against dissidents living abroad. The UN system and States should recognize transnational repression as a specific and mounting threat to human rights and create mechanisms aimed at countering it.

Recommendations

1 - To the Algerian government

2- To third party states

Reject politically motivated extradition requests

3- To the United Nations

Methodology

This report examines the transnational repression of human rights defenders (HRDs), activists, journalists, and political dissidents by Algerian authorities from 2020 to 2024. This period is marked by a clampdown on civic space following the Hirak movement.

CIHRS conducted 19 interviews with stakeholders including HRDs, political dissidents, journalists, lawyers, human rights researchers and others, covering 21 cases of individuals harassed or repressed across borders. The majority of those interviewed by CIHRS are refugees or asylum seekers currently residing outside of Algeria. These interviews provided first-hand accounts and detailed insights into the experiences of those affected by transnational repression. Conducted in French, Arabic, and English without interpreters, the interviews took place via secure online platforms between January and September 2024.

The research involved an extensive review of primary sources to corroborate the information gathered from interviews and to provide a solid factual basis for the analysis. Primary sources reviewed included courts’ judgements, extradition requests, and other judicial documents. Additionally, CIHRS reviewed statements and reports from human rights organizations and political leaders, including speeches and official declarations from Algerian officials.

Introduction

The Hirak movement began in February 2019, marking a watershed moment in Algeria's modern history. Sparked by widespread frustration with corruption, economic stagnation, and the announcement of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika's candidacy for a fifth term, the movement quickly gained momentum, drawing millions of Algerians into the streets. The Hirak was characterized by its inclusivity and non-violent nature, uniting people across different social, economic, and regional backgrounds.

For many Algerians, the Hirak movement represented a powerful expression of their collective aspirations for genuine democratic reforms and an end to the entrenched system of cronyism and autocracy. The protests were driven by a deep-seated desire for a more open, just, and accountable government. Slogans such as ‘Yetnahaw Gaa’ (‘They all must go’) encapsulated the demand for a complete overhaul of the political system, reflecting widespread disillusionment with the ruling elite. Despite initial attempts by the government to quell the protests through a combination of concessions and repression, the Hirak movement persisted. The resignation of President Bouteflika in April 2019 was a significant victory for the protesters, but it did not signal the end of their demands. The movement continued to call for the removal of the entire ruling elite, the establishment of a civilian government, and comprehensive political reforms.

The optimism and momentum generated by the Hirak movement were met with increasing repression from the state, leading to a rollback of the limited freedoms that existed prior to the protests. Since President Tebboune’s election in 2019, Algerian authorities have escalated their repression of fundamental freedoms, targeting freedoms of speech, press, association, assembly, and movement.[5] Major civil society organizations have been dissolved, opposition political parties suspended, and independent media outlets shut down.[6] Restrictive legislation has been employed to prosecute human rights defenders, activists, journalists, and lawyers. According to activists monitoring arrests, there are currently hundreds of political prisoners languishing in jail. Instances of stifling dissenting opinions from journalists have been rampant, such as the case of Ihsane El Kadi, arrested in December 2022. On 2 April 2023, El Kadi was sentenced to 5 years in prison on charges of ‘receiving funds for political propaganda’ and ‘harming national security’, stemming from his receipt of funds from his daughter and his work as a journalist.[7] The Algiers Court of Appeal increased the sentence to seven years, of which two were suspended.[8]

Algerian authorities often rely on vague legal provisions and flawed trial procedures to implement this repression. Article 87 bis of the Penal Code, which broadly defines terrorism crimes, is often invoked to justify the arrest and imprisonment of dissidents.[9] Charges such as ‘undermining national unity’ and ‘incitement to unarmed gatherings’ are also used to criminalize peaceful activism and dissent. Trials are marred by procedural irregularities and lack due process.

On 18 May 2021, the Supreme Security Council under the leadership of President Abdelmadjid Tebboune classified as ‘terrorist organizations’ the political opposition group RACHAD and the Movement for the Self-Determination of the Kabylie region (MAK). The same month, the Ministry of Interior initiated legal proceedings to dissolve the Youth Action Rally (RAJ), a prominent civil society organization. Notably, RAJ's president, Abdelouahab Fersaoui, had previously endured a seven-month imprisonment from October 2019 to May 2020 on charges of ‘harming the integrity of the national territory’ after expressing criticism of government policies on Facebook. The ministry's petition against RAJ accused the organization of deviating from its foundational objectives, alleging involvement in ‘suspicious activities with foreigners’and politically driven actions designed to foment chaos and disturb public order. These accusations culminated in the administrative court of Algiers's decision on 13 October 2021 to order the dissolution of RAJ. On 20 January 2023, the Algerian League for the Defense of Human Rights (LADDH) learned of its dissolution through social media channels. LADDH was entirely excluded from the procedure initiated on 4 May 2022, when the Ministry of the Interior submitted a preliminary request for the dissolution of LADDH to the administrative court of Algiers.

After effectively closing all spaces for dissent within Algeria, authorities have expanded their repressive reach to target dissidents abroad regardless of geographical boundaries. The extreme measures taken by the Algerian government to stifle dissent extend beyond its borders, as evidenced by cases where activists have been abducted from neighboring countries and forcibly returned to Algeria for trial and detention. Surveillance, harassment, and travel restrictions are employed to limit the movements and activities of dissidents, their families, and their associates. Additionally, activists and journalists who seek asylum abroad face threats of arrest, deportation, abduction, and intimidation due to international arrest warrants or extradition requests made to their host countries, as well as pressure from Algerian consulates.

The Algerian diaspora, known for its support of the Hirak movement and calls for democratic reforms, suffers from ongoing surveillance, persecution, and intimidation by Algerian authorities. These actions are often justified by repeated and vague charges related to cooperation with ‘terrorist entities’ or claims of national security threats posed by individuals and groups abroad with connections inside Algeria. This strategy enables the government to discredit the opposition, framing it as a threat to national security and public order.

By labeling the opposition movements and civil society organizations as terrorist entities, including the political opposition group RACHAD and the MAK, the Algerian authorities were able to use this designation to justify severe measures against these groups and their members as well as individuals accused of association with them whether in Algeria or abroad.

CIHRS is not in a position to determine whether Rachad and MAK, or any other organization or their individual members, may be liable to prosecution for activities considered illegitimate under international law, such as incitement to hatred or engagement in acts of violence. However, it clearly monitored how the Algerian authorities use the accusation of links to these organizations as an entry point for reprisals against opponents, human rights defenders, journalists, and artists inside and outside of Algeria, issuing judicial rulings against them and throwing them in prison. CIHRS also views the Algerian authorities’ classification of these organizations as terrorist, as well as the subsequent prosecution of their members and those associated on terrorism charges, as a violation of international law in several ways.

First, this classification does not conform with the principles of necessity and proportionality. States need to ensure that the prohibition or dissolution of an association is always a measure of last resort, such as when an association has engaged in conduct that creates an imminent threat of violence or other grave violation of the law. The UN Human Rights Committee has said that the state must demonstrate the precise nature of the threat as well as the fact that the restrictions are ‘necessary to avert a real, and not only hypothetical danger to national security’.[10] Prohibiting or dissolving an association must also not be used to address minor infractions. According to international standards, national security can be a justification for limiting the exercise of the right to association. However, as highlighted by the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism and the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, governments must not use legitimate interests, including preventing terrorism, as ‘smokescreens for hiding the true purpose of the limitations’, such as suppressing opposition, or to justify repressive practices against their populations.[11] Algerian authorities have thus infringed on the right to freedom of association without demonstrating imminent or real threat from these organizations.

Second, according to CIHRS’ review of several court cases, authorities prosecuted activists and HRDs for their alleged membership in Rachad and MAK, through unfounded charges and without respect for fair trial rights. If Algerian authorities are to try those suspected of instigating and participating in deadly violence in Algeria, it should be on the basis of solid, individualized evidence. Under international human rights law, governments may penalize incitement to violence, hatred, or discrimination but only under laws that provide a clear, narrow, and specific definition of what constitutes incitement, and that are consistent with protecting the right to freedom of expression. Prosecuting incitement to violence should be limited to cases in which the incitement is intentional and directly linked to the violence. Prosecutions for incitement to hatred or discrimination should never include peaceful advocacy for the rights of a segment of the population or regional autonomy or independence.

1- Algeria’s Pressure on Foreign Countries to Harass or Surrender Activists

In pursuit of silencing dissent and maintaining control, the Algerian government has employed various transnational tactics to harass and repress activists abroad. These methods include leveraging illegitimate extradition requests and using diplomatic channels to restrict free movement of dissidents. By exerting diplomatic pressure, Algeria seeks to harass, intimidate, and forcibly return activists who criticize the regime or expose its corruption. This approach violates international human rights laws and undermines the principle of non-refoulement, which protects individuals from being returned to countries where they face serious harm. The following sections explore the specific cases of individuals targeted by these tactics, illustrating the extent of Algeria's influence and the complicity of foreign governments in these repressive measures.

Use of Extradition Requests and International Arrest Warrants to Prosecute Activists

One of the most prevalent forms of transnational repression used by Algerian authorities is the issuance of extradition requests for Algerian nationals residing outside the country. These requests are often based on flimsy grounds, aiming to circumvent international legal standards and secure the unlawful removal of individuals from foreign countries, often leading to their detention and forced return to Algeria.

Such was the case of Mohamed Benhlima, an Algerian national who sought asylum in Spain. As a former military officer and whistleblower, he exposed corruption among high-ranking Algerian officials through his YouTube channel. He also took part in the Hirak protests against the Algerian government that began in 2019. Benhalima arrived in Spain on 1 September 2019, with a valid Schengen visa. At this time, he applied for asylum, and the Spanish authorities granted him a residence permit that was later renewed, valid until 5 November 2021. In January and March 2021, Algerian courts sentenced Benhalima in absentia to a total of 20 years in prison. Charges against him included ‘participation in a terrorist group’ under Article 87 bis 3 of the Algerian Penal Code, and ‘publishing fake news undermining national unity’ under Article 196 bis, both of which are often used by Algeria to silence dissent. CIHRS reviewed one of the verdicts issued by the tribunal in Tipaza, dated 9 March 2021. It imposed a 10-year prison sentence for Benhalima's online activities, including videos exposing military corruption, which are protected under the right to freedom of expression.

On 23 August 2021, Benhalima was summoned to a police station in Bilbao, Spain. Fearing extradition to Algeria, he fled to France shortly afterward. His fear was fueled by the previous extradition of another former military officer and asylum seeker, Mohamed Abdellah, from Spain to Algeria on 20 August 2021. On 14 March 2022, Benhlima was arrested in the Spanish city of Zaragoza, as he had left France, again out of fear of extradition to Algeria and was interned in a Foreigner's Detention Center in the city of Valencia. At this time, two confidential reports were submitted by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to the Spanish government on 21 March 2022. The reports recommended that Mr. Benhlima's asylum request undergo a thorough review through a standard procedure rather than a hasty rejection, citing credible risks of torture and Algeria's recognized practice of criminalizing peaceful opposition.[12]

On 24 March 2022, at around 7 p.m., Benhlima's lawyers were notified of his expulsion order and quickly filed an urgent request for a temporary suspension with the Spanish National Court (Audiencia Nacional), which was denied. It was later revealed that at that time, Benhalima was already being escorted to Algeria on a plane. In an interview with CIHRS, Benhlima’s lawyer in Spain, Mr. Alejandro Gámez Selma, stated that typically an individual detained in Spain in such a case would be held for a longer period, and such a rushed extradition is highly irregular. According to Mr. Selma:

In order to achieve [the extradition of Benhlima] as fast as possible and to avoid any judicial supervision, the Kingdom of Spain deliberately chose a preferential administrative procedure, avoided asking for guarantees from the Algerian Government, and set up a specific urgent plan for [his extradition.

According to Mr. Selma, Spanish police authorities opened an urgent administrative file for Benh lima’s arrest, on the grounds, per the Spanish police, of infringing Article 54.1.a. of Spanish Immigration Law 4/2000, alleging that Benhlima had taken part in ‘activities contrary to public security or which may be harmful for Spanish relationships with foreign states’. However, Mr. Selma stated that Spanish authorities have not provided any proof of ‘use or incitement of violence or any other action’taken by Benhlima that could be considered as a threat to public security. Given Benhl ima’s sentencing in absentia to the death penalty in 2021, his extradition to Algeria posed a very serious threat to his life and dignity. Despite this, Spanish officials apparently ignored the risk that he would be subjected to serious human rights violations upon his extradition to Algeria.

Upon his extradition to Algeria, in a blatant violation of his right not to be compelled to testify against himself, Ennahar TV in Algeria broadcasted a video on 27 March 2022 in which Benhlima confessed to conspiracy against the state and claimed he had not been mistreated while in custody.[13] Prior to his deportation, Benhlima had released a video from a detention center in Valencia, in which he warns that any future videos following his forced return to Algeria that show him confessing would have been coerced.

Spanish authorities justified Benhlima's deportation by citing his close association with Mohamed Abdellah. Abdellah had sought asylum in Spain in April 2019 but was forcibly returned to Algeria on 21 August 2021, under similar circumstances and for a similar alleged violation of Article 54.1.a. of Spanish Immigration Law 4/2000. Transferred from the Zona Franca detention center in Barcelona to Almeria, he was then put on a boat to Ghazaouet, Algeria, where he was immediately taken to Algiers and detained. This rapid deportation, authorized by Spanish Minister of the Interior Fernando Grande-Marlaska, sparked significant outrage among Algerians and international human rights activists. Abdellah, an ex-gendarme, had been living in exile in Spain since 2018, where he continued his peaceful campaign against the Algerian military, exposing numerous cases of corruption involving high-ranking officers. As of writing this report, Abdellah is still detained in an Algerian prison. His case as well as Benhlima’s underscore the troubling complicity between Spain and the Algerian regime, as Abdallah was handed over without any judicial oversight, based on unsubstantiated accusations of terrorism. Once in Algerian custody, the authorities subjected both to torture and ill-treatment.

The extradition of Algerian whistleblowers Mohamed Abdellah and Mohamed Benhlima by Spanish authorities represents a stark violation of international human rights law and exemplifies the practice of transnational repression by Algeria. While governments have the right, under international law, to remove individuals from their territory for legitimate reasons, expulsions and deportations can constitute transnational repression when the individual’s country of origin has sought the removal for illegitimate reasons or when due process rights were violated. In the cases of Benhlima and Abdellah, both individuals who sought asylum in Spain, invoking protections under the 1951 Refugee Convention, to which Spain is a party. The principle of non-refoulement, a cornerstone of international human rights law, prohibits the return of asylum seekers to countries where they may face serious harm, including torture and inhumane treatment. Spain's decision to forcibly return Abdellah and Benhlima to Algeria, where they were at significant risk of persecution and torture, blatantly disregards this principle. Moreover, these deportations occurred without sufficient judicial oversight, infringing on the right to a fair trial guaranteed by Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

France’s position on the extradition request for activist Mourad Dhina was different. Dhina is an Algerian physicist and activist, currently serving as the Executive Director of Alkarama and a co-founder of the RACHAD movement. On 16 January 2012, Dhina was arrested in Paris based on an extradition request from Algeria, alleging his involvement in a terrorist organization in the 1990s. However, French courts identified significant inconsistencies and unreliable evidence, including coerced testimonies, and ultimately concluded that the charges were politically motivated to silence Dhina’s opposition to the Algerian regime. In June 2012, the Paris Court of Appeals rejected the extradition request due to the lack of credible evidence.

In the case of Abdou Semmar, an Algerian journalist and refugee in France, the Algerian authorities issued approximately seven international arrest warrants. Semmar fled Algeria to Tunisia before moving to France in January 2019. His decision to seek asylum was driven by continuous threats and harassment in retaliation for his journalistic activities, particularly his investigations into government corruption. In October 2022, the Dar El Beïda court in Algiers sentenced him to death in absentia, accusing him of espionage and disseminating false information that could endanger national security or public order. These charges were linked to his online media platform, Algérie Part. Semmar was tried in absentia without legal representation and was unable to access his case file, similar to many of the cases documented by CIHRS. Following the verdict, the judge issued an international arrest warrant against him. In his interview with CIHRS on 20 March 2024, Semmar suspected that the charges are related to his 2020 investigation into Sonatrach, the state-owned oil and gas company. Despite being in France, Semmar continues to face legal and personal pressures extending to his family as well, as documented in the following section.[14]

Hamza Kherroubi, also a member of the National Independent Union of Electricity and Gas Workers (SNATEG) and spokesperson for the Confederation of Productive Forces Unions (COSYFOP) in Algeria, who has been living in Belgium since 2020, was sentenced in absentia to 20 years in prison in Algeria in December 2023. Due to his union activities, Kherroubi is facing charges of establishing, organizing, and managing a terrorist or sabotage group with the aim of committing terrorist and sabotage acts, under Article 87 bis of the Penal Code. He is also accused of ‘using information and communication technologies to recruit individuals for a terrorist organization’, and ‘publishing and promoting false and malicious news among the public that could harm public order’.

Kherroubi’s case involves several other individuals, many of whom Kherroubi told the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS) he has no connection with. It seems that the Algerian authorities are intentionally grouping unrelated individuals into terrorism-related cases, likely to inflate the perceived threat of terrorism in Algeria and accelerate the sentencing process.[15]

Use of Diplomatic Channels to Hamper Freedom of Movement

Rachid Mesli is an Algerian human rights lawyer and activist residing in Geneva, Switzerland. Mesli currently serves as the Legal Director of Alkarama, an organization he founded in 2005 which defends victims of arbitrary arrest, disappearance, and torture.[16] He is also one of the co-founders of the RACHAD movement in 2007. In 1996, Mesli was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment on charges of ‘encouraging terrorism’. One year after his release in 1999, Mesli left Algeria for Switzerland, fearing for his and his family’s safety. In 2002, Mesli was accused and subsequently charged in absentia by Algerian authorities of being part of an ‘armed terrorist group’ operating abroad.[17] This charge came after two men arrested in March 2002 were reportedly tortured by Algerian security forces into falsely confessing ties with Mesli and the armed group. Following this, Algerian authorities issued an international arrest warrant in April 2002. As a result, Mesli has been unable to travel without concerns for his safety, as evidenced by his arrest on 19 August 2015 at the Swiss-Italian border by Italian police following his 2002 arrest warrant. He was later allowed to return to Switzerland on 16 September 2015 after an extradition request filed by Algiers on 7 September was deemed ‘vague and incomplete’.

According to Mesli’s statement to CIHRS, he has been tried in Algerian courts multiple times in absentia, with sentences ranging from 20 years in prison to the death penalty. He has found himself banned from entering several countries, including Turkey. In May 2023, he was arrested at a Turkish airport and deported back to Switzerland.

At the airport, I was handed a document stating that I am banned from entering for 5 years. The document did not state the reasons for the ban, but I think it is due to Algeria’s pressure on Turkish authorities …. The noose is tightening around each of us.

Interview with Rachid Mesli on 5 March 2024

Ultimately, the grounds for Mesli’s entry ban to Turkey lack transparency or apparent legal justification. Mesli's multiple in absentia convictions in Algeria, particularly those resulting in severe penalties including lengthy prison sentences and the death penalty, violate his right to a fair trial. Article 14 of the ICCPR guarantees the right to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent, and impartial tribunal. Absentia trials, especially those conducted without the defendant's knowledge or presence, fail to meet these standards.

Another case is S.T.[18], a refugee in Europe, who has faced significant human rights violations due to his peaceful political opposition to the Algerian regime. He was included on a list of terrorists identified by Algerian authorities. In September 2023, S.T. attempted to travel to France but was informed at the airport that he was prohibited from entering the country. CIHRS reviewed this prohibition paper, based on a decision from the French Minister of the Interior and Overseas, which cited S.T.'s activities as a threat to public order and national security, and potentially harmful to diplomatic relations between France and Algeria.[19]

This designation has had a profound impact on S.T.'s daily life. He encounters significant obstacles in obtaining visas for other countries and faces rejections from some countries when trying to open bank accounts. These barriers not only impede his right to freedom of movement but also infringe on his economic and social rights. S.T. stated:

What the Algerian regime is doing to human rights defenders, journalists, and political opposition is social assassination.

Pressure on activists through Algerian consulates in foreign countries

In the cases of Mohamed Benhlima, Mohamed Abdellah and S.T., the diplomatic relations of both Spain and France, respectively, with Algeria were a deciding factor for their treatment by European states. In other cases, such as that of Rachid Mesli, diplomatic pressure was exerted but failed to lead to the extradition of a political dissident back to Algeria. It seems Algeria leverages its diplomatic influence in order to target specific individuals. Consulates summon Algerian citizens, clearly threaten them, and force them to suspend their opposition activities.

In his interview with CIHRS, Algerian artist Kamal Sehaki, who has been living in Canada since 2018, recounts his disturbing encounter with the Algerian consulate in Montreal, highlighting different tactics of transnational repression. Sehaki is an artist, cameraman, and short film director originally from the Kabylie region in Algeria whose artistic endeavors have been deeply rooted in his community. He continued his work and maintained connections with the Kabyle diaspora. In late April 2024, Sehaki began receiving persistent calls from an individual at the Algerian consulate, requesting a meeting and complimenting his artistic talent. The meeting took place on 11 May 2024, in a public space in Montreal. However, the conversation quickly shifted to his connections with the Movement for the Self-Determination of Kabylie (MAK). Sehaki clarified that, although he is not a member of MAK, he has worked with them professionally by filming their events and protests in Canada. The consular representative’s questions focused intensively on MAK’s activities and its financing:

He asked me about who pays me in the MAK. He asked me to stop filming any events by MAK, stop any contact with my friends who are part of MAK. He even named two of my friends who are members of MAK in Canada.

Interview with Kamal Sehaki on 1 July 2024

He suggested that the Algerian government could help boost my career if I stopped any relation with MAK. The consulate could give me contracts, and I could start filming events at the consulate.

Further coercion included offering Sehaki to sign a document disassociating himself from MAK and ‘pledging to be a good citizen’. The consular representative also hinted at facilitating Sehaki's return to Algeria, contingent on signing the document:

He told me about a paper I would sign, where I would quit MAK, say that I will be a good citizen, and apologize… He also told me that if I wanted to return to the country, it would be very simple; just sign an agreement.

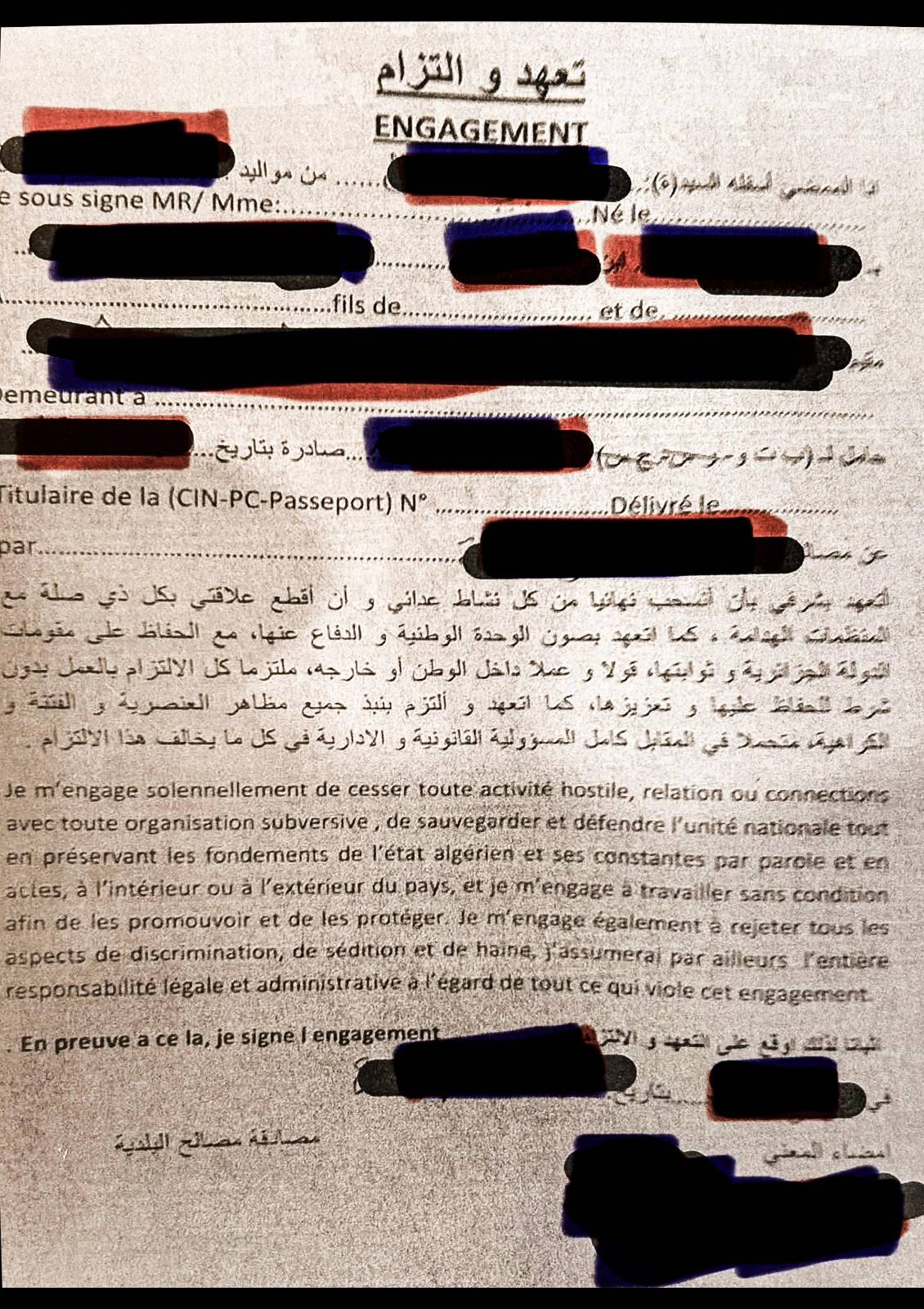

Sehaki provided CIHRS with a copy of the statement received by another individual, which consisted of a form to fill out. CIHRS was not able to independently verify the authenticity of the document. The form, in Arabic and French, required signatories to adhere to stipulations set forth by the Algerian authorities and demanded personal identification details, including the signatory's name, birthdate, place of residence, and identification numbers from national ID, passport, or other official documents. The document contained the following language:

‘I solemnly pledge to cease all hostile activities, relationships, or connections with any subversive organization, to safeguard and defend national unity while preserving the foundations of the Algerian state and its principles in word and deed, both within and outside the country. I also commit to working unconditionally to promote and protect these principles. I further commit to rejecting all aspects of discrimination, sedition, and hatred. Additionally, I will assume full legal and administrative responsibility for anything that violates this commitment.’

Kamal Sehaki's testimony reveals the methods employed by the Algerian government to monitor and suppress political dissent among the Kabyle community abroad. By targeting individuals like Sehaki under the guise of offering professional support, the government aims to gather intelligence and undermine opposition movements. This strategy not only seeks to stifle political activism but also serves to intimidate those who might sympathize with or support such causes. Such tactics of transnational repression extend beyond mere surveillance. They involve direct interference in the lives of expatriates, leveraging their professional and personal aspirations to coerce compliance.

2- Coordinating repressive efforts with neighboring countries

On 25 August 2021, Slimane Bouhafs, an Amazigh activist and Christian convert, was kidnapped from his home in Tunis. Bouhafs, who had previously spent two years in prison between 2016 and 2018 for ‘offending the prophet of Islam’, had been registered as a refugee with the United Nations in Tunisia since 2020. On the day of his disappearance, witnesses reported seeing three unidentified men carrying a seemingly unconscious Bouhafs out of his residence and into a waiting car. He was forcibly disappeared for a period of four days. His family members then learned that he was detained in a police station in Algiers.

Algerian authorities charged him with ten counts, including several terrorism related charges, as well as offending Islam, propagating discriminatory and hate speech, attacking the security and unity of the country, spreading fake news, inciting an unarmed gathering, and receiving foreign funding to undermine state security and stability.

The first instance tribunal of Dar Beida in Algiers tried him on 16 December 2022, together with two other activists, and sentenced him to three years in prison under three counts: spreading fake news, undermining state unity, and propagating hate and discriminatory speech under articles 196 bis and 79 of the Penal Code and Article 31 of Law N. 20-05 of 28 April 2020, on preventing and combating discrimination and hate speech, respectively. The judgment, which CIHRS reviewed, does not explain the grounds for the sentence and the specific acts that form the basis of the allegations against Bouhafs. In a letter of response to UN human rights experts asking the government to clarify the legal grounds for his arrest and detention, Algeria claimed that they discovered evidence linking him to the Movement for the Self-Determination of Kabylie (Mouvement pour l’auto-determination de la Kabylie, MAK), which authorities arbitrarily classified as terrorist in April 2021.[20] The lack of grounds for Bouhafs’ sentence clearly contravene his right to be presumed innocent.

During his trial, Bouhafs testified that he was tortured during his detention at the hands of unknown men and declared that the confessions used against him were extracted under torture.

Bouhafs’ trial is illegal under international human rights law. His abduction and subsequent reappearance in Algeria indicate a transnational effort to suppress dissent and silence activists, raising serious questions about the involvement of external actors in his forced removal from Tunisia.

Zakaria Hannache is a human rights activist whose case is representative of the complicity of neighboring countries in coordinating repressive efforts with the Algerian government. Hannache has been deeply involved in documenting and advocating against human rights violations, particularly those related to the Hirak protest movement. His work has made him a prominent target for government repression.

Hannache was first arrested on 18 February 2022 by plainclothes officers who searched his home and confiscated his phone. He was subsequently charged with ‘praising terrorism’, ‘undermining national unity’, and ‘receiving funds from an institution inside or outside the country’. These charges carry severe penalties, including potentially life imprisonment or the death penalty. The charges stemmed from his activities in documenting and publishing information on the arrests and trials of peaceful activists and protesters. After being detained for six weeks in Algeria, he was provisionally released on bail in March 2022.

In August 2022, Hannache left Algeria for Tunisia. Despite this, the legal harassment against him continued unabated. Hannache was advised not to return to Algeria due to the high risk of arrest and further prosecution on spurious charges. He became recognized as a refugee by the UNHCR on 14 November 2022.

On 9 November 2022, Hannache was notified by his lawyers of a sudden and suspicious replacement of the investigative judge at the Sidi M'Hamed court one day before the trial, on 10 November. The new judge had no time to review the extensive case file, yet the hearing was pushed forward, underscoring the authorities' intent to disadvantage Hannache and deny him a fair trial.

He was subjected to intense surveillance and targeted intimidation by Tunisian state security forces, in apparent collusion with Algeria’s repressive apparatus. On 14 November 2022, Tunisian anti-terrorist police appeared at a location Hannache regularly visited under the pretext of searching for a patient. This visit coincided precisely with Hannache’s usual appointment time, indicating that he was under close surveillance. He told CHIRS:

On November 14, 2022, I obtained the asylum seeker's card. B ut at the same time, the Tunisian anti-terrorist brigade showed up at [this location] looking for a patient of Arab nationality, on the same day and at the same time as my usual appointment.

CIHRS Interview with Zakaria Hannache, 11 April 2024.

Since that day, I was changing apartments every three days, then every week, and then every month. All my movements were with a lawyer. This relentless need to move not only disrupted my life but also imposed severe financial burdens.

In March 2023, while still in Tunisia, Hannache was convicted in absentia and sentenced to three years in prison by an Algiers court. An international arrest warrant was issued at this time against him.

It is worth noting that Hanish also struggled (under pressure from Algeria) to obtain refugee status. Initially, his resettlement request to France was met with complications, resulting in a suspension of the process and the redirection of his case to Canada.

On 23 November he traveled to Romania temporarily; on 19 December 2023, UNHCR Canada agreed to resettle him, and Hannache moved to Canada. From there he continues to document human rights abuses and the repression of peaceful dissent.

3- Travel bans (on leaving Algeria) to clamp down on activists residing abroad

Algerian authorities have employed travel ban measures to prevent dissidents and human rights defenders residing abroad from leaving Algeria as soon as they return temporarily for family visits. Their families may also face harassment and intimidation, in a deliberate attempt by the Algerian government to impose a web of repression that ensnares activists and their families, regardless of their physical location, and punishes them for any form of cross-border communication or support.

This approach, based on comprehensive monitoring of the online activities of Algerian activists abroad, and their arrest or prosecution upon their return to Algeria, aims to spread fear among the diaspora community, and may have a chilling effect on its ability to express opposition or even solidarity with the victims of repression at home.

On 19 February 2022, border police prevented Lazhar Zouaimia[21], a member of Amnesty International in Canada and a technician at a public electricity utility in Quebec, from boarding a plane to Montreal at the Constantine airport, without legal justification or an order to restrict his right to travel, which prevented him from challenging these restrictions before the court.

The police at the airport detained him and the airport officer instructed him to hand over his phone without presenting an order from the prosecutor. Police then transferred Zouaimia to the military barracks in Constantine, where they questioned him about his participation in the Hirak protest movement in Montreal and his alleged connections with the Movement for the Self-determination of Kabylie (MAK) and RACHAD. On 22 February 2022, a judge at the first instance Court of Constantine ordered Zouaimia’s pretrial detention on charges of ‘praising and funding a terrorist organization’ under A rticle 87 bis of the Penal Code. Zouaimia was provisionally released on 30 March. On 6 April 2022, a judge in the same court changed the charge to ‘harming the integrity of the national territory’ under Article 79 of the Penal Code.

During a second attempt to travel back to Canada, on 9 April 2022 at Houari Boumediene Airport in Algiers, Zouaimia was accompanied by two representatives from the Canadian embassy and his lawyer. An Algerian law enforcement officer took him aside, detained him in an office for hours, and then released him after his flight had left. Authorities also blocked him from boarding another flight to Barcelona later that day. Zouaimia was finally able to leave Algeria and return to Canada on 5 May 2022. After returning to Canada, he told CIHRS that he learned there that he had been sentenced in absentia to five years in prison.

I was part of the Hirak in Canada. I didn't participate in all the activities but there were numerous gatherings, demonstrations, and online forums discussing the developments of the Hirak movement. I joined whenever I had the time, but others were more fully committed, participating 100%.

CIHRS Interview with Lazhar Zouaimia, 2 February 2024

Similarly, Djamila Bentouis, an artist residing in France, was jailed for her exercise of free speech against the Algerian government upon her temporary return to Algeria.

Djamila Bentouis is a midwife poet and singer who participated in the Hirak movement, writing poetry and patriotic songs. In Paris, she often recited her poetry at Place de la République. Her songs related to the Hirak have been widely shared on social media. On 25 February 2024, Bentouis traveled to Algeria to visit her ailing mother. Upon her arrival at Algiers airport, she was arrested and questioned by police, who confiscated her travel documents. She was released on 28 February 2024, with a requirement to report to the Dar El Beïda judicial police. There, she faced further interrogation about her involvement in the Hirak movement, her political views, and a song she had written and performed.

Several websites and pages have shared the video of the song, and the CIHRS has translated its lyrics into Arabic and English.

On 3 March 2024, Djamila Bentouis was presented before the prosecutor at the Sidi Mhamed court. The prosecutor subsequently transferred her case to the investigating judge. Following this, the judge issued a detention order against her, citing three charges: Article 87 bis, which pertains to ‘membership in a terrorist entity’; ‘incitement to unarmed gathering’; and ‘undermining national unity’. Consequently, Bentouis was transferred to Koléa prison. On 13 March 2024, the indictment chamber confirmed the detention order, upholding the charges against her. However, there was a significant development on 28 May 2024, when the indictment chamber of the Algiers court decided to drop the charge under Article 87 bis. The two remaining charges of incitement to unarmed gathering and undermining national unity were confirmed. The case was then referred to the Sidi Mhamed correctional court.

Bentouis’s trial scheduled for 20 June 2024 was postponed to 27 June. On 4 July 2024, she was sentenced to two years in prison and a fine of 100,000 Algerian dinars under the charges of ‘undermining the security and unity of the country’ and ‘inciting an unarmed gathering’. International human rights standards, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), protect the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and association. The detention of individuals exercising these rights, such as Djamila and Zouaimia, appears to conflict with these standards. The charges related to ‘undermining the integrity and security of the State’ and ‘inciting unarmed gatherings’ can be broadly interpreted and may be used to target political activists and human rights defenders.

The monitoring of diaspora activists’ political activities and publications, their arrests upon returning to Algeria, and the travel bans imposed on them when they attempt to leave Algerian territory underscore the extensive measures taken by the Algerian government to suppress dissent, extending transnationally.

4- Family harassment

If the Algerian authorities are unable to get ahold of opponents abroad through international arrest warrants, extradition requests, pressure from Algerian consulates, or restrictions on their right to move or travel, the authorities resort to pressuring their families and their network of supporters inside Algeria to force opponents to return or stop and disrupt their opposition activities abroad. This may extend to the exposure of relatives of political activists and human rights defenders to arbitrary detention, interrogation, surveillance, and fabricated charges of terrorism and spreading false information. This approach not only targets families but also undermines dissidents’ support networks, creating a chilling effect on activism and free expression in Algeria.

Mohamed Larbi Zitout is a former Algerian diplomat who sought asylum in London in 1995 after revealing severe human rights violations by Algerian state forces during the civil war (1993-2000). Since then, he has been an outspoken political dissident, advocating for the establishment of rule of law and democracy in Algeria, with a specific focus on ending the military’s grip on the state. This advocacy, which he conducts through the RACHAD Movement, has led to his designation as a ‘terrorist’ by Algerian authorities. On 30 March 2022, Mohamed’s brother, Abderrahmane Zitout, was arrested by the Algerian authorities from his clothing store located on the ground floor of his family residence. Following the raid, Abderrahmane was taken to an undisclosed location, and his family was unable to locate his whereabouts until 4 April 2022, when they discovered he was being held at El Harrach prison in the outskirts of Algiers.[22]

During his initial days in custody, Abderrahmane was subjected to prolonged interrogation at the central police station in Algiers. The questioning focused on his relationship with his brother, their political alignments, and involvement in the Hirak movement. On 5 April 2022, Abderrahmane was brought before the public prosecutor at the Sidi-Mhamed court, where he faced charges of terrorism and spreading false information. These accusations were reportedly based on the coerced testimony of former military officer Mohamed Benhlima, implicating Abderrahmane in crimes of terrorism and subversion. Despite the lack of material evidence and Abderrahmane's denial of these allegations, the judge ordered his pretrial detention. This decision was later upheld by an appeals court on 20 April 2022.

Abderrahmane’s defense lawyers consistently argued that the charges were politically motivated, stemming solely from Benhlima’s coerced testimony (Benhlima later retracted his testimony, citing torture). Despite this, a second bail request on 9 June 2022 was also rejected. In a bid to contest his arbitrary detention, Abderrahmane commenced a hunger strike from 14 August to 1 September 2022. His health severely deteriorated during this period, leading to his emergency hospitalization until 11 September 2022. In February 2023 Abderrahmane Zitout went on a hunger strike again.[23] This was his third such protest since being jailed.

Subsequently, Abderrahmane Zitout stood trial at the Dar el Beida Criminal Court on 12 July 2023. The verdict, delivered on 23 July 2023, indicated that he was initially charged with several offenses, including:

Despite these charges, the absence of concrete evidence in the case led the court to convict Zitout of ‘spreading false news with the intent to disrupt public order and security’ and ‘insulting a constituted body’. Consequently, he was sentenced to two years in prison. His detention, widely viewed as a tactic to silence political opposition and intimidate activists, further raises serious concerns about Algeria's adherence to international legal standards and the protection of civil liberties. On 20 October 2023, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention issued an opinion on the case stating that ‘Mr. Zitout is being detained on a discriminatory basis, including because of his family ties and in retaliation for the activism and political views of his exiled family member. This is a case of guilt by association’.[24]

Amira Bouraoui is a gynecologist and has been an activist since 2011. Bouraoui has a well-documented history of being targeted by the Algerian authorities due to her activism and critiques of the state and state officials online.

On 4 May 2021, a tribunal in Cheraga, Algeria convicted Amira Bouraoui to two separate two-year prison sentences, the first for ‘offending the principles of Islam’ on social media, and the second for ‘insulting the president of the Republic’ online. These sentences were ordered to be served starting in May 2023. Bouraoui fled across the Tunisian border in February 2023 to escape potential incarceration by the Algerian government, challenging the travel ban issued against her.

On 3 February 2023, Bouraoui was arrested for illegal entry into Tunisia at the Tunis airport, as she was attempting to flee to France with her French passport. Having dual Algerian-French nationality, Bouraoui was able to avoid extradition to Algeria with the assistance of the French embassy in Tunis, who ultimately secured her ability to leave for France on 8 February 2023. Her departure ignited a diplomatic dispute between Algiers and Paris. On 24 February 2023, a Tunisian court sentenced her in absentia to three months in prison for illegal entry into Tunisia. On 7 November 2023, an Algerian court in Constantine sentenced her to 10 years in prison in absentia.

Within days, the Algerian authorities arrested Bouraoui’s mother, Khadidja Bouraoui, aged 71, as well as her cousin, Yacine Bentayeb; Djamel Miassi, the taxi driver who drove Bouraoui to Tunisia; journalist Mustapha Bendjama; and a border officer[25] on charges of ‘forming a criminal association, illegal exit from the national territory, and organizing illegal immigration through a criminal network’, on the basis of helping Amira Bouraoui to leave the country.[26] In a TV interview, Amira Bouraoui stated that she crossed the border without assistance from Bendjama or any border officer.

The Algerian authorities first arrested Mustapha Bendjama in his Annaba newsroom on 8 February 2023 and charged him with ‘criminal organization to commit illegal immigration’ and ‘smuggling of migrants within an organized gang’ under articles 176, 177 and 303 bis of the Penal Code. Algerian authorities used private conversations found on Mustapha Bendjama’s confiscated phone as the basis of further investigations, according to his lawyer. Bendjama has been repeatedly barred from leaving the country[27] and the court sentenced him to 6 months in prison on charges of helping Bouraoui flee to France.

While Amira Bouraoui’s mother was released and placed under judicial supervision on 20 February 2023, Bentayeb (her cousin) was detained on 10 February 2023 and placed in pretrial detention on 19 February 2023. He was released from Boussouf Prison in Constantine on 7 November 2023. The Constantine court later imposed a three-year prison term on the border police officer (Ali Takaid), and a one-year suspended sentence on Bouraoui's 71-year-old mother, Khadidja.

In a separate case, Bendjama was charged with receiving foreign or domestic funding to commit public order offenses under Article 95 bis of the Algerian Penal Code.[28] Additionally, he was charged with publishing classified information under Article 38 of Order no. 21-09 on the protection of administrative information and documents. The same was case for Canadian researcher Raouf Farah.[29]

Raouf Farrah, an analyst for the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, was arrested on 14 February while visiting family in Annaba. He faced charges similar to Bendjama under the Penal Code, as authorities had alleged a criminal connection between the two. His father, Sebti Farrah, 67, was also detained and provisionally released on 13 April 2023. On 26 October 2023 both were prosecuted. The court condemned them to eight months in prison and added a suspended sentence for an additional year. During the hearing on 22 August 2023, Farrah's lawyer, Kouceila Zerguine, explained that his client had never published any classified document nor had he received any funds. He had, however, issued funds to Mr Bendjama, and these funds were in no way likely to prejudice public order. On 26 October 2023, Bouraoui and Bendjama were both placed under travel bans; at least a dozen activists face similar indefinite travel restrictions, despite legal provisions limiting such measures. After Amira Bouraoui fled to France under diplomatic protection, and journalist Mustapha Bendjama faced additional charges of assisting her escape to France. Ultimately, all these co-defendants were accused of ‘forming a criminal association, illegal exit from the national territory, and organizing illegal immigration through a criminal network’.

After an in absentia ruling was issued in Algeria to imprison journalist Abdo Semmar, a refugee in France, the repression extended to his two children residing in Algeria. After Semmar left Algeria in 2019, his children visited him twice; in the summer of 2021, he was granted family reunification in France, which should have allowed his children to join him permanently there. Algerian authorities, however, obstructed their reunification in France by preventing his children at the airport from leaving the country. Semmar’s case is indicative of the broader harassment and intimidation tactics employed by the Algerian authorities against HRDs abroad.

Similarly, the case of Dr. Benbabaali Mohammed further highlights how the Algerian authorities’ transnational repression extends to families of the targeted person. Benbabaali, a France-based anesthetist and intensive care doctor and political activist, reported to CIHRS that in early 2023, his family members and associates in Algeria faced harassment and interrogation by police. The incidents began when Benbabaali’s brother and a friend were detained in early 2023 by the Algerian police and held in police custody for 72 hours. During their detention, they were interrogated about financial transactions with Benbabaali, his connections in Algeria, and his affiliations with political movements such as RACHAD and MAK. Dr. Benbabaali told CIHRS:

They asked my brother, “Does your brother in France send money to people in Algeria? Who are his friends in Algeria? Did you know that he is involved with RACHAD and MAK?

The police later interrogated more members of Benbabaali’s circles - another brother, his sister-in-law and brother- in-law, and a friend – about his views and activism. This systematic pattern of interrogations indicates an effort to gather information on Dr. Benbabaali’s political activities through his family and friends, highlighting the reach of transnational repression.

In May 2023, Dr. Benbabaali’s wife experienced similar harassment. Upon her arrival in Algeria, plainclothes judicial police officers arrived at her family house in a white VW Polo and instructed her to report to the police station the next morning. During her interrogation, the police inquired about Dr. Benbabaali’s personal life, including his political activities, his religious practices, and his associations with different political and religious groups. They also asked invasive personal questions. Dr. Benbabaali said to CIHRS:

They [the police] asked my wife if I beat her, if I was politically active in the 90s, if I was Islamist, if I wore a long beard, if I was involved with the FIS, who I am talking to.

After the interrogation, she was asked to sign a police statement before being allowed to leave.

Journalist and activist Manar Mansri told CIHRS that in November 2018 she was forced to flee to Tunisia due to the increasing pressure and threats she faced in response to her activism in Algeria, where she worked as a journalist at the daily newspaper Minbar Al-Gharb and Al-Jumhuriya, as well as the head of the local news department at Al-Rai daily newspaper. She is also the founder of Ayn al-Makan News Network, an alternative media network in Algeria, which she reported was shut down by authorities after the arrest of several of its correspondents. Before she fled the country, her brother was arrested and her family faced constant harassment. In 2019, she relocated to Turkey, where she continued her work as a journalist for Asharq Al-Awssat TV and established the Network for the Defense of Blogging Rights in Algeria. Despite at least three extradition requests sent by the Algerian government, Turkish authorities have refused to hand her over. Nevertheless, she remains at significant risk of being forcibly returned to Algeria.

In February 2022, Manar Mansri was officially designated as a terrorist in Algeria's national list of terrorist persons and entities, published in the Official Journal.[30] This designation was based on her alleged affiliation with RACHAD. On 2 January 2023, Manar Mansri, (along with Mohamed Zitout and Amir Boukhors) was sentenced in absentia to 20 years in prison by the criminal court of first instance in Dar El-Beida, Algiers. The sentence also included a fine of one million Algerian dinars (approximately 7500 USD) and confirmed an international arrest warrant against her. She was convicted for alleged subversive acts and endangering the unity and security of Algeria during forest fires that occurred on 6 November 2020[31] in the Tipaza province, although Manar Mansri had already fled Algeria two years prior. The fires were part of a series of blazes that broke out simultaneously in eleven provinces across Algeria; judicial investigations later alleged these were the result of criminal acts of arson intended to destabilize the country.

In February 2024, Mansri’s brother was detained by police on his way to work and subjected to a 12-hour session of intrusive questioning including about her activities and personal questions about their relationship and other details. Mansri said:

The police asked my brother. “Does your sister send money? Who takes care of her daughter in Algeria? How is she? What kind of books does she read? When did she start her activism?

Interview with Manar Mansri, 8 May 2024

Ahmed Mansri, the head of the Algerian League for the Defense of Human Rights in Tiaret, was arrested on 8 October 2023, in retaliation for meeting with the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Association and Peaceful Assembly during an official visit to Algeria. Judicial police in Tiaret searched his home, seizing all his electronic devices, and they also arrested his wife, releasing her the same day. On 11 October 2023, Mansri appeared before the prosecutor of the First Instance Tribunal in Ksar Chellala, Tiaret province, where he was remanded in prison the same day and charged with ‘disseminating false information’, ‘inciting an unarmed gathering’, and ‘participation in a terrorist organization’ under articles 196-1, 100-1, and 87 bis of the Penal Code. Mansri was sentenced to six months in prison on 14 January 2024, three of which were suspended, leading to his release on the same day.

In his interview with CIHRS on 26 September 2024, Mansouri indicated that he decided to flee Algeria to avoid further persecution. He traveled to another country, where he applied for asylum with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. His wife and children later joined him, and he is still awaiting a final decision on his refugee status.

Following Mansri’s departure from Algeria, his family continued to face harassment and intimidation from the Algerian government. On 22 September 2024, around 10:30 AM, security services in the Ksar El Chelala district apprehended Ahmed’s brother in front of his store. He was taken to his home where a search was conducted, and his wife and minor children were also arrested. At 11:15 AM, the security services arrested his father and another brother, conducting a search of the father’s house.

Ahmed Mansri’s family was taken to the Ksar Chelala district police station where the two minors were released on-site, while the others were interrogated about Ahmed’s whereabouts and who had assisted him with leaving Algeria. Family members denied knowing where he was located or who had helped him escape. Although his father, one brother, and the sister-in-law were released later, one of his brothers was transferred to the Tiaret provincial security offices. There he was questioned about Ahmed's whereabouts and accused of aiding his brother in fleeing. He denied these allegations. Security services informed his brother that Ahmed had been posting content on social media deemed detrimental to national interest and security. They warned that if these posts continued, the authorities would systematically arrest family members. Ahmed’s brother was finally released at 11:00 PM that day.

All cases detailed in this report are characterized by the Algerian government’s use of diplomatic pressure on other states with the aim of persecuting HRDs, activists, journalists, and other political dissidents together with their families, friends, and other associates.

5- Algeria's use of conspiracy theories to stifle dissent inside and outside the country

The Algerian government has strategically employed a narrative of conspiracy to justify the widespread repression of HRDs and activists. Transnational repression plays a central role in creating a narrative that opposition and activism are part of a larger conspiracy against the state, hatched by organizations whose members are based inside and outside of Algeria.

In the following sections, two judicial cases reviewed by CIHRS highlight instances in which authorities prosecuted ten activists and HRDS (some of who are living abroad) on charges of ‘terrorism’ and ‘undermining state security and unity’. In both cases, individuals were prosecuted for their alleged ties to Rachad and MAK without any evidence of involvement in violent actions or incitement to hatred, discrimination, or violence.

2021 fires and the killing of Djamel Ben Smail

The Djamel Ben Smail assassination case, while initially centered on events within Algeria, took on a transnational dimension as Algerian authorities extended their reach to prosecute activists living abroad, linking them to a broader conspiracy theory. The authorities accused individuals living outside Algeria of being involved in the lynching of Ben Smail and the fires in Kabylie, in 2021, even though some of them were living in countries like Canada and France at the time of the events. This approach allowed Algerian authorities to target members and sympathizers of the Movement for the Self-Determination of Kabylie (MAK) under expanded anti-terrorism laws, using tenuous connections and alleged affiliations as the justification for harsh penalties, including death sentences.

In November 2022, the Criminal Tribunal of First Instance in Dar El Beida, Algiers, sentenced to death 54 individuals, including five in absentia and one woman, and for their alleged roles in the lynching of activist Djamel Ben Smail in Larbaâ Nath Iraten, Tizi Ouzou, on 11 August 2021, during the series of fires that devastated the Kabylie region and killed nearly a hundred people. At least five convicted individuals who were outside of Algeria at the time were prosecuted on the basis of their alleged connections to the Movement for the Self-Determination of Kabylie (MAK), a group designated as a ‘terrorist’ in 2021 and whose leadership is primarily based abroad in France. Many of the defendants, part of a group of 116 individuals tried simultaneously, faced accusations linked to their affiliation with or sympathy toward MAK.

According to CIHRS' review of the indictment issued by the indictment chamber on 16 June 2022, the prosecution of MAK-affiliated individuals was based on a broad interpretation of anti-terrorism laws. Without proof of their involvement in any criminal act, dozens of individuals faced prosecution merely for their affiliation, sympathy toward, or social media following of MAK. We also note that one person was prosecuted solely for having friends associated with MAK, illustrating the expansive application of anti-terrorism legislation to stifle political dissent.

Human rights groups have decried violations of fair trial standards during these proceedings. The trials were conducted in a manner that lacked transparency and fairness, with allegations that at least two of the defendants tried in absentia were not properly informed of charges or trial schedules, in violation of fair trial standards.[32] The court proceedings were closed to observers, including families of the victims, further undermining the transparency of the judicial process.

Two lawyers for the defendants reported several procedural violations. According to one of the defense lawyers, the judge relied heavily on statements made to the police and videos taken by the defendants during the lynching of Djamel Ben Smail. At least fifteen defendants claimed their statements were extracted under duress. Mohamed Laaskri, one of the convicted individuals, told the judge he was tortured while in custody, with methods including electric shocks and waterboarding, and threatened with rape. The judge dismissed these torture claims, stating that it was the defendant's responsibility to file a complaint with the prosecutor. Other fair trial violations included the judge's refusal to hear witnesses and the decision to hold the trial behind closed doors, excluding the families of the August 2021 victims.

At least four defendants sentenced to death were not even present in Algeria at the time of the events. Among them was Aksel Bellabbaci, a MAK executive living in France, who had not visited Algeria since August 2019. Trial records indicated that Bellabbaci's name appeared as a contact for MAK during detainee interrogations. Another defendant, Mourad Itim, a Canadian resident and manager of Taqvaylit TV, was convicted in absentia despite the fact he had not returned to Algeria since 2016. His conviction was linked to his media coverage of the fire events as well as allegedly sending funds from Canada to a member of MAK prior to these events in the Kabylie region.[33] The decision reviewed by CIHRS noted three separate transfers, amounting to a total of 260,000 dinars, approximately 2,000 USD.