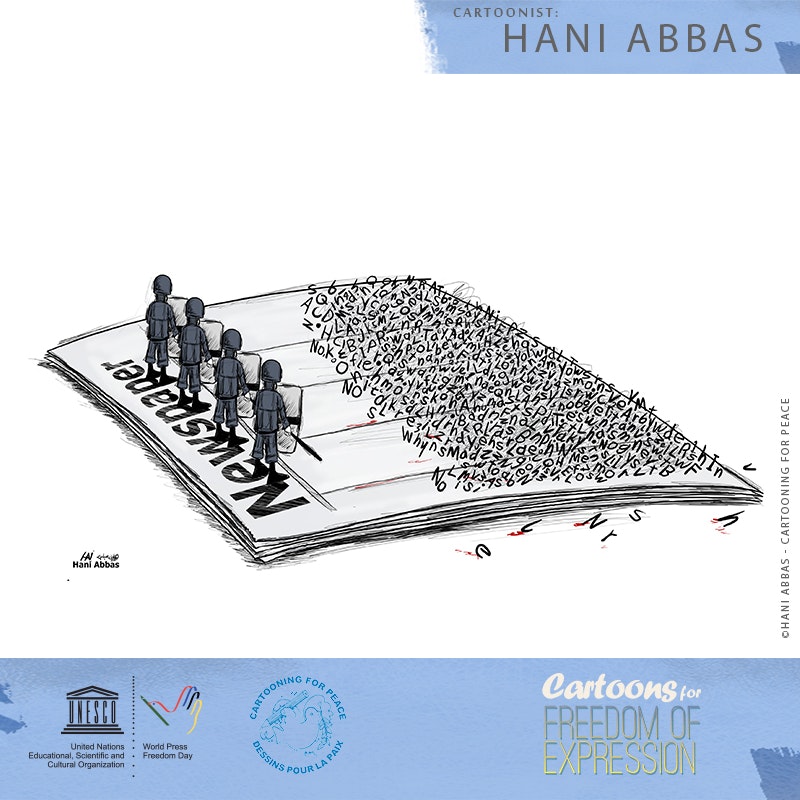

May 3rd marks the 28th anniversary of the annual World Press Freedom Day while also marking the first anniversary of the Egyptian state’s latest wide-scale campaign against press freedom. 98 websites have been blocked since May 3rd of last year, according to the latest survey by the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE). The Egyptian authorities persist in their refusal to disclose the entity responsible for blocking the websites and the legal framework under which it operates. At the same time, the Egyptian Parliament is fervently engaged in legalizing this extreme censorship, which is endemic to Egypt’s media landscape.

The Egyptian state’s stranglehold on the free flow of ideas and information has significantly tightened this year, with all media platforms falling within its purview: audio, visual, and print, state-owned and private. The state continues to restructure the Egyptian media market through systematic transfers of property with alleged security establishment involvement. Violations against journalists continued during throughout the year. Although the rate of violations has statistically decreased, the severity of these violations has worsened. There are now 21 journalists behind bars. Among these journalists are Adel Sabri, editor-in-chief of the independent website Masr al-Arabia. His detention was extended for 15 days on April 5th 2018, in State Security Case no. 441/2018. He is being held on four charges: spreading false news, incitement to violate the Constitution, joining a banned group, and inciting demonstrations.

Mohamed al-Sayyed Saleh, editor-in-chief of the widely-distributed, privately owned Egyptian daily Al-Masry Al- Youm was dismissed following a major controversy stemming from the paper’s presidential election coverage. The National Election Commission (NEC) filed a complaint against the paper for a headline and online content that it considered critical of the Egyptian state’s role in the elections. The Supreme Media Council then referred Salah and another reporter for investigation by the Syndicate of Journalists. The council fined the newspaper 50,000 Egyptian pounds and required it to publish an apology to the NEC.

For this year’s anniversary of World Press Freedom Day, the UN has chosen the theme “Keeping Power in Check: Media, Justice and The Rule of Law,” which stresses the role of an independent judiciary in safeguarding press freedom. The lack of an independent judiciary is one of the most serious crises facing press freedom in Egypt. This year witnessed the Supreme State Security Prosecution increasingly trying journalists in exceptional courts, with the most prominent of these cases being Case 441/2018, known as the “media cells of the Muslim Brotherhood” case.

The trial of investigative journalist and researcher Ismail al-Iskandarani continues before the Military Prosecution, to which he was suddenly referred on December 13 2017 after being held in pre-trial detention for over two years. He stands accused of ‘spreading false news’ and ‘joining an illegal group’ in apparent retaliation for his work specializing in marginalized communities in Egypt, most notably in the restive Sinai Peninsula. This year also witnessed final rulings against three Egyptian journalists: Abdullah Fakhrani and Samhi Mustafa of Rassd News Network (RNN) and Mohamed al-Adli, a broadcaster at Amgad satellite channel. The Court of Cassation (the country's highest appellate court) upheld their sentence of five years' imprisonment. The three journalists had been held in pretrial detention for five years after their arrest in August 2013.

The Public Prosecution has not ceased exploiting pre-trial detention as a retaliatory measure rather than simply as a precautionary measure to protect investigations. Detention periods of journalists are extended without any justification. One of the prominent examples of the excessive and retaliatory nature of pre-trial detention is that of photojournalist Mahmoud Abu Zeid, known as Shawkan, who is serving his fifth year in pre-detention for what is known as the "Raba’a dispersal” case, which is expected to be adjudicated in the coming months. Shawkan was awarded the 2018 International Press Freedom Prize by UNESCO; an award decried by the Egyptian Foreign Ministry in an official letter to the organization. This was not the first prize awarded to Shawkan. In 2016, he received the Press Freedom Award from the National Press Institute in Washington. His health continues to deteriorate in prison, as he suffers from Hepatitis C, a chronic disease requiring continuous medical attention. The prison authorities continue to refuse to allow him to receive urgent treatment for his worsening health condition.

Last April, Attorney General Nabil Sadiq issued a statement instructing prosecutors to monitor media publications or broadcasts and refer any violation to criminal investigation. The statement used the same incendiary term – “forces of evil” repeatedly used by President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in describing various media outlets during a speech he gave in April of 2017, in which he emphasized that he considers criticism of the police and army to be high treason. Sadiq did not specify or define the legal significance of the vague term, leaving it open to interpretation. Amidst the controversy, Al-Masry Al-Youm published a report explaining the president’s rage against the media by referencing the documentary film "Negative 1095", resulting in the arrest of Ahmed Tarek, the film’s editor. Salma Alaeddin, the director of the film, was also arrested.

Also in the aftermath of President al-Sisi’s “Forces of evil” speech, the Ministry of Interior filed a complaint against TV host Khairy Ramadan, presenter of the “Egypt Today” program on state television. The complaint accused Khairy of defaming the police after the episode discussed the low salaries of Egyptian police officers, whom Khairy had described as "honorable." After holding him in custody for two days, the prosecution released him on a 10,000 pound bail.

In its commemoration of World Press Freedom Day, the United Nations Secretariat stressed the importance of creating an enabling legal environment for press freedom. As of the present in Egypt, the press law regulating the media and the rights and obligations of journalists has been delayed for three years now. At the same time, a law regulating press and media institutions has been issued, which addresses the mandate of the Supreme Media Council and the two national agencies for press and media. This creates a situation where press freedom in Egypt is governed by new regulatory bodies formed by a new law in an attempt to control a climate that operates according to the provisions of an old law (Press Law No. 96/1996). This old law is incompatible with the new legislative structure for the press and media, thereby limiting the role of the new regulatory entities to censorship and control rather than creating an appropriate legal environment conducive to the work of media professionals.

Since its formation, the Supreme Media Council has been preoccupied with forming “censorship partnerships” with journalist and media unions, in order for the Egyptian state to expand its censorship capacities over all information and ideas directed to the public. Thus the Supreme Media Council, rather than enabling the press, is hostile to it, stifling any alternative narratives and strengthening the monopoly of the state narrative over information and ideas. This explains the delay in the issuance of the Freedom of Information Act, which the Supreme Council was working on through a committee it had formed this year. Many journalists are awaiting this law, hoping it will facilitate their daily work and their access to official information.

This is likely the same logic governing the recent actions of the State Information Service (SIS), especially after head of the Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies, journalist Diaa Rashwan, assumed its presidency in 2017. The SIS played a new supervisory role over all publications and broadcasts about the Egyptian state in foreign media. This has resulted in many disputes between the SIS and a number of international media outlets, including the BBC, Reuters, and others. There was a significant conflict over the discrepancy in the number of victims in the Oasis Terrorist Attack on October 20th of last year, with international media outlets maligned by the SIS for claiming there were a higher number of police officers killed than was reported by national and local Egyptian media outlets.. Another significant conflict emerged in March of this year when Egyptian authorities, upon a call from the SIS, deported the Times of London correspondent Bel Trew, alleging she was working without a permit, in violation of SIS regulations. As evidenced by the aforementioned disputes, the legal environment governing press and media freedom in Egypt is not, by any means, enabling; but rather, it is restrictive and dangerous for journalists and media professionals, jeopardizing their safety and freedom.

While the ‘rule of law’ was meticulously applied by the Egyptian state authorities to censor media coverage, no similar political will was reflected to use the rule of law to provide legal guarantees for press freedom. Instead of creating an impartial regulatory framework, the authorities sought to fully dismantle and structure the legislative, legal and institutional media framework in favor of the state narrative. For example, in Article 71 of the Egyptian Constitution (2014) pretrial detention is completely prohibited with three exceptions: discrimination between citizens, incitement to violence, and defamation of individuals. However, according to the chair of the Journalists’ Syndicate, Abdel Mohsen Salameh, various Egyptian laws cumulatively contain 35 articles allowing for the imprisonment of journalists on the basis of their publications; none of these laws were revised to make them adhere to the Constitution.

One of the most prominent recent examples of a journalist being imprisoned under unconstitutional laws is the detention of journalist Moataz Wadnan of the Arabic Huffington Post, in Case no. 441/2018. He was detained after publishing an interview with former government auditor Hisham Genena, who is currently imprisoned because of the interview. The interview was about the presidential campaign of candidate Sami Anan, former chief of staff of the Egyptian Armed Forces, who was disqualified from the nomination and held in detention. Egyptian authorities considered the interview to be spreading lies and undermining national stability.

The government’s emphasis on the “rule of law” when censoring media and imprisoning journalists comes during the same month marking the first anniversary of one of the state’s most blatant violations of the rule of law: the Egyptian security forces’ storming of the Journalists Syndicate headquarters. The raid occurred in May of last year following a major crisis between the syndicate and the Ministry of Interior, following which the former chair and two council members in the Syndicate were referred to an urgent trial.

Similarly, the Supreme Media Council contributed to breaching the rule of law when it relinquished its role in protecting competition and preventing monopoly in the media market. This occurred in the context of widely held suspicions of direct interference by sovereign authorities in the large-scale transfer of ownership in the media market. This includes the ownership transfer of the Egyptian Media Group, which owns a large number of influential media and press channels, to Eagle Capital, an investment company affiliated with the General Intelligence Service, according to reports. Eagle Capital is owned by former Minister of Investment Dalia Khorshid, who is the wife of Central Bank Governor Tarek Amer.

Similarly, Falcon Group, a prominent private security company, bought Al-Hayat television networks owned by Dr. Sayed Badawi, head of the liberal Wafd Party. Falcon’s board of directors is chaired by a former deputy head of military intelligence. These unsettling deals have not received any attention from the Supreme Media Council despite the suspicions revolving around them. There has been no attempt by the council to even simply identify the facts surrounding those ownership transfers and their impact on free and transparent competition in the media market.

Finally, the aforementioned violations of the right to a free press and media, as well as dangers to which journalists working in Egypt are exposed, were noted in the Reporters Without Borders (RSF)’s 2018 World Press Freedom Index report. With this in mind, the undersigned organizations, on the anniversary of the World Press Freedom Day, reaffirm their support of the UN Secretary-General's call on governments, with the Egyptian government foremost among them, to promote press freedom and protect journalists.

Signatory Organizations

- Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE)

- Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS)

- Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF)

- Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR)

- Nadeem Center for the Rehabilitation of Victim of Violence and Torture

Share this Post