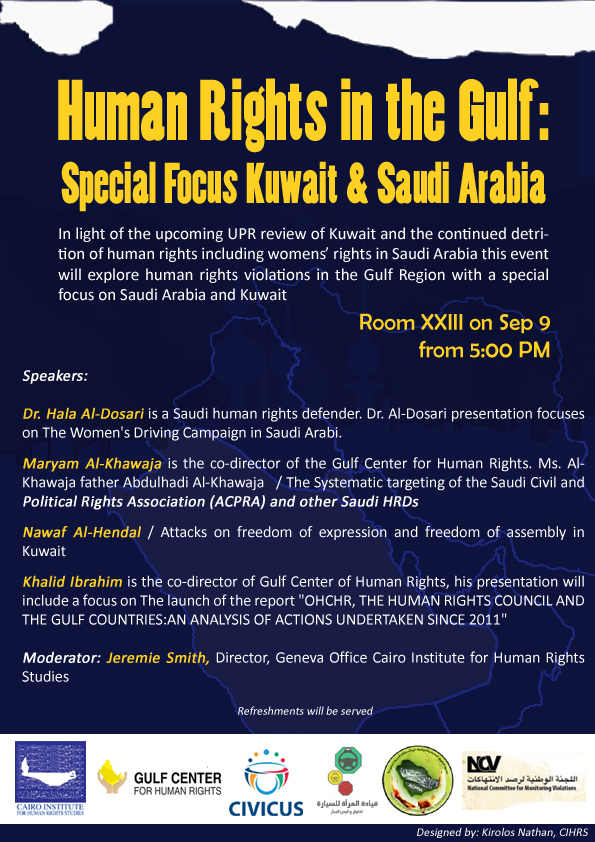

On 9 September, the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS), in cooperation with the Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR), the National Committee to Monitor Violations–Kuwait (NCV), the World Alliance for Citizen Participation (CIVICUS), the Saudi Civil and Political Rights Association (ACPRA), as well as representatives from the Saudi Women’s Driving Campaign, organized a side event on the status of human rights in the Arab Gulf, with a focus on Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

On 9 September, the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS), in cooperation with the Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR), the National Committee to Monitor Violations–Kuwait (NCV), the World Alliance for Citizen Participation (CIVICUS), the Saudi Civil and Political Rights Association (ACPRA), as well as representatives from the Saudi Women’s Driving Campaign, organized a side event on the status of human rights in the Arab Gulf, with a focus on Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

The side event, organized on the sidelines of the 27th session of the UN Human Rights Council (HRC), currently convened in Geneva, was attended by several rights activists, EU representatives, representatives from Switzerland and the Netherlands, OHCHR representatives from the MENA office, as well as the media.

Taking part in the seminar were Khalid Ibrahim, the co-director of the Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR); Hala al-Dosari, a Saudi rights advocate with the Saudi Women’s Driving Campaign; and Nawaf Al-Hendal with the NCV. Jeremie Smith, the director of the Geneva office of CIHRS, chaired the event. Maryam Alkhawaja was scheduled to speak, but the Bahraini authorities detained her just days earlier.

Jeremie Smith opened up the meeting by recognizing the constant threats and hostility faced by human rights defenders in the Gulf because of their work and their cooperation with and participation in UN activities. He saluted all seminar participants while urging them to exercise caution.

Khaled Ibrahim began his talk by criticizing the weak engagement of UN instruments and the HRC in dealing with the deteriorating state of rights and liberties in the Gulf region and the ongoing attacks against human rights defenders. He noted that he was standing in for rights defender Maryam Alkhawaja, who was scheduled to take part in the seminar to discuss human rights in Saudi Arabia, but was currently detained by the Bahraini authorities.

During his talk, Ibrahim reviewed the most recent report issued by the Gulf Center, “OHCHR, the Human Rights Council and the Gulf States: An Analysis of Actions Undertaken Since 2011″, issued in tandem with the side event. The report analyzes the most significant measures taken by the OHCHR and its various instruments since 2011 with regard to the situation in the UAE, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. It found that while action was strong in relation to Bahrain, other Gulf countries particularly Oman, Qatar, and Kuwait, did not receive as much attention despite the grave human rights situation in those countries.

The report also includes a record of the most important intergovernmental communications, national field visit reports, the most significant conclusions of the reports of convention bodies, and the most prominent measures and resolutions taken by the HRC based on its efforts in these countries.

In addition, the report looks at the challenges hindering the operation of civil society organizations, some recommendations to overcome them, and government obstacles preventing organizations from gathering information and documenting incidents, as is the case of Bahrain and Saudi Arabia. As another example, in Oman, all the administrators for a Facebook page dealing with human rights have been detained.

The report recommends strengthening outreach and networking through the appointment of Arabic speakers in the OHCHR, promoting cooperation between the HRC and civil society groups, and inviting rights defenders to speak on specific countries and relying on them for information to the OHCHR.

In regard to human rights in Saudi Arabia, Ibrahim mentioned wide-scale violations and the systematic targeting of human rights defenders, noting that criminals in Saudi Arabia enjoy more rights than human rights defenders. He said that those working in human rights are always at risk of facing ready-made charges, while terrorism laws are drafted specifically to attack human rights defenders.

Shifting to the topic of freedom of opinion and expression in Saudi Arabia, Ibrahim noted that all media are state owned while social media such as Facebook and Twitter are heavily monitored, as the state is tightening its control over all forms of online expression.

During the seminar, Hala al-Dosari gave a detailed presentation about the campaign to allow women to drive in Saudi Arabia. Dosari noted that the Saudi authorities continue to discriminate against women while the government sends out mixed messages regarding its commitment to human rights conventions and women’s rights. The authorities also continue to impose policies and measures that violate the basic law of governance in Saudi Arabia, which provides for equality of all citizens.

Dosari explained that historically, women were not officially prohibited from driving in Saudi Arabia, but were subject to an unofficial driving ban. In 1990, however, the Interior Ministry issued an official ban in response to 47 Saudi women driving their cars in Riyadh in protest against driving restrictions. A fatwa was then issued describing women’s driving as an act of evil, which promotes mixing of the sexes, and increases the risk of moral degeneracy. The women participating in the protest were arrested and questioned for several hours, after which they and their legal guardians were made to sign a pledge not to engage in the same act again. The women were suspended from their jobs, given a two-year travel ban, and subjected to a vicious media smear campaign.

According to Dosari, in 2001 the authorities arrested Manal al-Sherif after she uploaded a video to the internet calling on Saudi women to obtain international drivers licenses; she was only released after her father presented the king with a petition signed by members of his tribe. Shortly thereafter, the police stopped two women driving from Jeddah to Mecca. A court sentenced them to lashing, but the sentence was temporarily suspended.

Dosari added that last year a group of women activists in several cities planned a campaign on social media to collect signatures from women demanding the right to drive and declaring they would start driving on October 26, 2013. Within three days, the petition had gathered more than 17,000 signatures before the government blocked the campaign’s website. The police and the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice also arrested women participating in the campaign, detaining them for several hours in some cases. Their legal guardians were summoned to sign a pledge that the women would not attempt to drive again. Some of the activists also received phone calls from an Interior Ministry representative asking them to end the campaign and threatening sanctions against any person who challenged the driving ban. The activists publicized the warning from the Interior Ministry and advised women to avoid driving on October 26, stating they would try at a later date.

In the conclusion of her presentation, Dosari discussed the proposal of three women members of the Shura Council regarding lifting the ban on women driving. Although the council was involved in reviewing the Traffic law, the women were subjected to a smear campaign orchestrated by the traditional wing of the council. Dosari stressed that most activists involved in peaceful activities against the ban on women’s driving were arrested or questioned and had their cars confiscated. She lauded the efforts of the HRC and its members in pressuring for a resolution on the issue by citing international conventions and treaties shortly before the Universal Periodic Review of Saudi Arabia, which constituted a strong lobbying instrument against the government. Dosari argued that continued pressure would guarantee effective action.

Nawaf Al-Hendal focused on the issues of freedom of expression and assembly, human rights defenders and the Bidoun (the indigenous people of Kuwait never given citizenship by the government) in light of Kuwait’s upcoming Universal Periodic Review. Al-Hendal stated that more than 100,000 stateless Bidoun people live in Kuwait, and the refusal to issue them with citizenship means they are deprived of official documents such as birth and marriage certificates as well as economic and social rights such as the right to work, education, and medical treatment. The Bidoun are also prohibited from advancing their rights through peaceful means, including through the media, social media, and peaceful demonstrations; violators face five to ten years in prison under national security laws.

Al-Hendal noted that more than 200 people currently face charges of insulting the royal family, blasphemy charges are becoming more frequent, and there is a new tendency to convict people on charges of insulting the judiciary and judicial system. Al-Hendal explained that such charges are being used to retaliate against human rights defenders, citing the case of Mohammed al-Ajami, a member of the NCV, who was charged with defaming Islam on Twitter.

Al-Hendal pointed to the revocation of citizenship as a punitive measure in Kuwait, directed especially against rights and political activists. Recently, citizenship was revoked from 15 individuals and their families, thus denying them social and economic rights.

Finally, Al-Hendal criticized Gulf security treaties that give Gulf governments the right to exchange private information about citizens and residents. The treaties also allow arrest and travel bans that are applicable across all member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council.

Share this Post