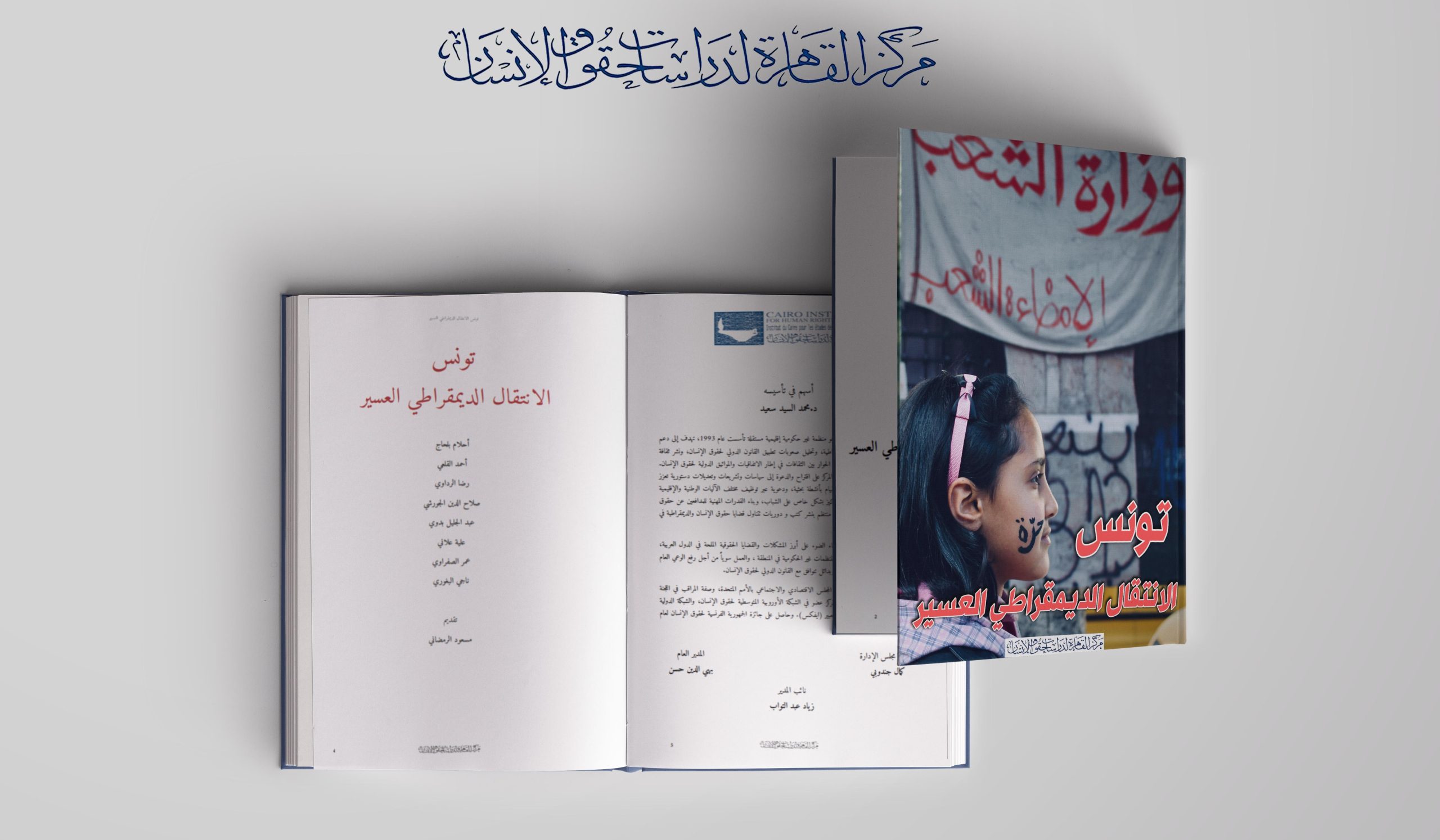

Today, January 14th 2018, marks the 7th anniversary of the Tunisian revolution, which ousted a deeply entrenched dictatorship while averting the chaos, civil strife, and bloodshed that afflicted other Arab Spring countries. Yet despite these hard fought victories, major setbacks and challenges have marred Tunisia’s transition to democracy, as detailed in a new book released this morning by the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS) titled Tunisia: The Difficult Democratic Transition.

In eight essays, Tunisian researchers and advocates examine crucial aspects of the ongoing transition, including social movements and economic development, the role of women, transitional justice, civil society, Islamic ideologies and movements, the Tunisian constitution, and media freedom. Following an introductory overview by CIHRS’ legal representative in Tunisia and rights activist Massoud Romdhani, Tunisian economist Abdeljalil Badawi notes the failure of successive governments to replace the Ben Ali regime with a fair, democratic and development-oriented system, as evidenced by the persistence and recent escalation of social protest movements. Furthermore, as highlighted by Tunisian feminist Ahlem Belhadj, any fair and democratic governance must acknowledge the vital role of women, not only in sparking the revolution but also in jointly upholding, together with men, human rights and liberties in Tunisia during the transitional phase.

As Tunisia forges ahead into the next year, the violations of the past must be exposed and the violators brought to justice, if the nascent democratic system is to prevent a reemergence of past abuses and genuinely break with authoritarianism, asserts Omar Safraoui, the chair of the independent National Coordination for Transitional Justice. If justice is to be achieved, there no alternative but to make transitional justice independent of state structures, Safraoui contends, echoing a central demand of Tunisian civil society. Yet in the seven years since the revolution, successive Tunisian governments have disregarded this and other demands of civil society. Civil society itself has been undermined by the expansion of the Interior Ministry’s jurisdiction over the licensing of civic associations, as detailed by Ahmed Galai, a former member in the executive body of the Tunisian League in Defense of Human Rights.

In their exploration of Islamic ideologies and movements, researchers Alaya Allani and Slaheddine Jourchi conclude that Ennahda – despite its connections to Islamic movements outside of the Tunisian state like the Muslim Brotherhood as well as jihadi Salafism and other extremist trends – will gradually adapt to the Tunisian context. Alani believes that the liberal wing of Ennahda, led by Rachid Ghannouchi, will lead to a break from the thought and organization of the Muslim Brotherhood. In his essay, Jourchi notes that Ennahda’s abandonment of secrecy for public service, as well as its constitution as a party that believes in democracy and does not exclusively speak in the name of Islam, reflect the beginning of its incorporation of democracy.

In his analysis on the Tunisian constitution, rights advocate Ridha Raddaoui notes that despite the advances made by the 2014 constitution in this regard, concerns remain due to ambiguity in constitutional concepts and terms in relation to rights and freedoms. The same is true of media freedom according to Naji al-Baghouri, the head of the Tunisian Journalists’ Syndicate, who asserts that laws regulating this sector “still need to be reviewed to comport with international laws.” He adds that while numerous structural and legal reforms have contributed to press freedom and protection for journalists, there is still potential for regression, as Tunisia is not yet grounded in strong institutions.

The potential for regression, the undoing of Tunisia’s democratic gains, looms as the country today commemorates the uprising that reverberated around the world, initiating the Arab Spring that swept throughout the region. Although Tunisia emerged as a relative success story, its democratic future remains contested. Seven years and eight governments since the revolution, Tunisia’s democratic transition is under intensifying pressure from economic challenges, terrorist attacks, and the ancien regime’s desire to recapture control of the state. As the Tunisian people persist in their struggle for democracy, CIHRS and the contributors of this book maintain hope that this difficult transition will achieve the Tunisian revolution’s democratic aspirations.

Book currently available in Arabic.

Share this Post