Conclusions of a joint international conference

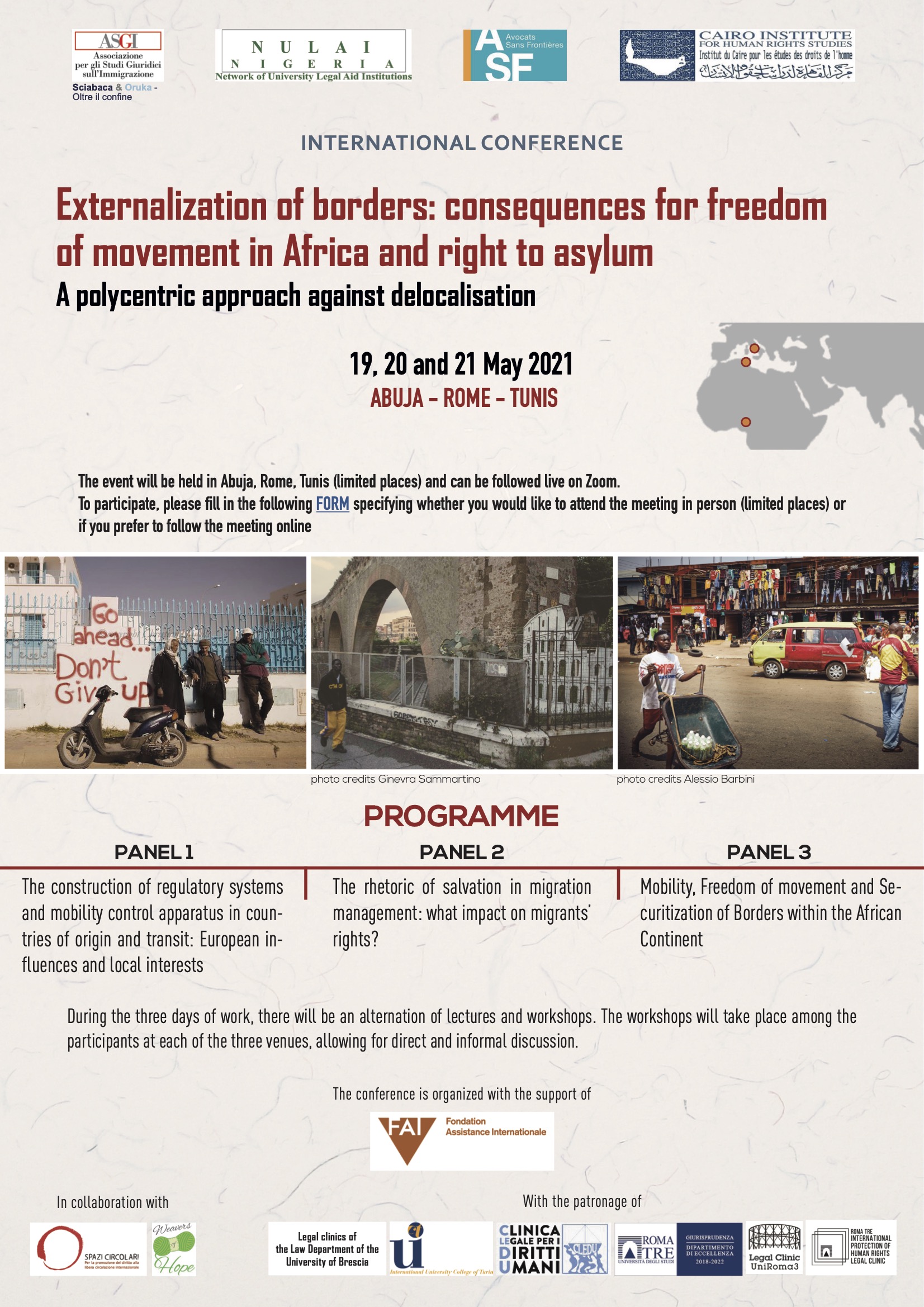

On 19, 20 and 21 May 2021, four human rights organisations – the Association for Juridical Studies on Migration (ASGI), the Network of University Legal Aid Institutions (NULAI Nigeria), Avocats sans Frontières (ASF) and the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS) – organised an international conference on “Border externalization policies: consequences on mobility in Africa and on the right to asylum”. During the conference, which took place simultaneously in Abuja, Roma, Tunis, and Libya; the organisations, in collaboration with 19 panelists and experts from Italy, Libya, Tunisia and Nigeria, reflected on how to develop transnational strategies to oppose externalization policies.

The following are the main conclusions of the joint reasoning developed during the conference:

As outlined repeatedly by rights organisations, the European Union (EU) and European Member States’ externalization policies severely restrict the freedom of movement of African citizens and as a result, constitute a serious infringement upon the fundamental right to asylum.

European externalization policies are part of a broader global migration management strategy, in which reinforcement of borders and security policies, and rushed expulsions and delocalization of border control, play a central role. As part of this strategy, European and African states, EU agencies, and a number of international institutions, intergovernmental agencies, private companies, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) all intervene in building up and defining systems to control and manage mobility.

In that regard, human rights organisations have observed that externalization policies are also taking advantage of the humanitarian mandate of international institutions and NGOs, and the tight link between development actions and migration management. In Tunisia, Libya and Nigeria, this work, which aimed at mitigating the effects of externalisation policies, has become an important source of legitimisation and implementation of these same policies.

The New Pact on Asylum and Migration has confirmed and reinforced a European approach that aims to confine the processes of selecting and determining the legal status of persons on the move outside the territory of the Union. This confinement takes place through cooperation with countries of origin and transit of migration flows, and through the development of a “legal fiction of non-entry” in transit areas on EU territory.

As the Conference was underway, media reports announced the possibility of the European Union concluding a new externalization agreement with Libya, according to which the Libyan government would prevent migrants from departing Libya and arriving to the southern borders of the EU, reportedly by strengthening the operational capacities of the Libyan Coast Guard. On 20 May, EU Commissioner for Home Affairs Ylva Johansson and Italian Minister of Interior Luciana Lamorgese travelled to Tunisia to reinforce the country’s joint maritime border control system and, at the same time, envision new mechanisms to intensify repatriations to Tunisia.

This alarming situation necessitates the development of new litigation strategies to identify the legal responsibilities of the different actors involved in violations migrants’ and refugees’ rights. To this end, it is essential to disseminate lessons learnt from the litigation and rights protection actions put in place by the organisers of the conference. It is also necessary to strengthen and expand litigation strategies that can be developed through transnational networks for the defence and promotion of migrants’ and refugees’ rights.

To that end, the organisers commit to strengthening cooperation and structuring joint action around the following objectives:

- Ensuring the accountability of African and European states for grave violations of the fundamental rights of people on the move, especially the right to liberty and security, including by advocating for the strengthening of human rights sanction mechanisms and universal jurisdiction;

- Challenging bilateral agreements and EU financial support for the implementation of border control and migration management aiming at containing human mobility;

- Challenging the violation of the right to asylum stemming from the application of summary asylum procedures and the facilitation of the readmission of asylum seekers in transit countries, stemming from the abusive application of the concepts of “safe third country” and “country of first asylum”;

- Engaging towards the publication of return agreements to allow the evaluation of their legality, especially in relation to the impact of their application on the fundamental rights of foreign citizens;

- Committing to legally monitor the activities of humanitarian actors – such as international institutions and NGOs – that legitimate externalization policies and to promote legal actions to ensure their accountability for violations of fundamental rights;

- Committing to monitor free trade agreements between African countries (within ECOWAS) and between EU and African countries (such as the EU Tunisia DCFTA), and highlight the ways in which it limits freedom of movement and economic activity and encourages human trafficking;

- Challenging the collection of personal data and the misuse of biometric control systems affecting the right to free movement and the right to asylum.

Cover photo: REUTERS/Darrin Zammit Lupi

Story of photo:

Migrants try to stay afloat after falling off their rubber dinghy during a rescue operation by the Malta-based NGO Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) ship in the central Mediterranean in international waters some 15 nautical miles off the coast of Zawiya in Libya, April 14, 2017. All 134 sub-Saharan migrants survived and were rescued by MOAS. Darrin Zammit Lupi: “I spent five weeks with the Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) on their ship, Phoenix, covering search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean. At the start of the Easter weekend we were on a routine rescue around 15 nautical miles off the Libyan coast. I was on the MOAS fast rubber boat with crew members handing out life jackets to a group of 134 Sub-Saharan migrants on a flimsy dinghy before we would transfer them to the Phoenix. I had one camera up to my eye to shoot some wide angle frames. Suddenly, one migrant balancing on the rim of a dinghy slipped sideways and like dominos several of his colleagues lost their balance and fell into the sea. I captured the whole sequence by keeping my finger on the shutter button. It was chaos. I kept shooting as the rescuers leapt into action, helping several of the migrants pull themselves onto our boat. I was grabbing hold of people with one hand and shooting with the other. Then, through my viewfinder, a few metres away, I noticed one man struggling more than the others, stretching out his arm towards us. I screamed to alert our specialist rescue swimmer that one man was going under. He reacted instantly, jumped in, and pulled the man to safety. Afterwards, I did a lot of soul searching. Should I have put down my cameras altogether and just grabbed hold of whoever I could? That evening I discussed it with the rescuers, who felt I’d done the right thing. Their job was to rescue lives. Mine was to document the harsh reality of what’s happening. Everyone survived that day.”

Share this Post